January is probably my least favourite month. It has all the darkness of December without the delights of Christmas to offset it. The weather usually does its worst and we know we are on the way out of the darkest days, but it seems to take forever to notice it. TV was always the go-to distraction in these dark days, but in recent years broadcasters and streaming services seem to have concentrated on presenting all their best stuff at the end of the previous year (probably for awards purposes), leaving the January cupboard comparatively bare. But not this year. For the first time in years, I have found plenty to engage me and already have four things for the 2023 shortlist!

Sunday nights on BBC1 is usually key at this particular moment and this year, with the third season of Happy Valley scheduled, a strong start was pretty much guaranteed. One of the things I look for in a good drama is ambiguity, but it had been somewhat lacking in the central Catherine Cawood (Sarah Lancashire) character in the first two seasons. She was always so impressively in command, the calm and reliable centre of events, taking everybody’s troubles upon her broad shoulders and coming out on top in the trickiest of circumstances. One thing she seemed to have no trace of was self-doubt and that was a clear flaw. This time round she began to realise that maybe she should have trusted others, especially her sister and grandson, rather than trying to protect them by keeping important information to herself, though it took a falling out with them both and the intervention of the ghost of her dead daughter to bring her to this realisation. Maybe, in the end, her implacable hatred of her nemesis, Tommy Lee Royce (James Norton) was also open to question. Not before the end titles, for sure, but maybe something for her to think about as she walked off into her retirement, like a western hero who had won the final showdown and was heading off into the sunset. A fine ending to a very fine series.

Also on BBC1 on Sundays in January (though it had started in December), and also in its third season, was Jack Thorne’s adaptation of Philip Pulman’s His Dark Materials. Throughout, it had been a brilliant and engaging mixture of fantasy adventure and theological/philosophical themes and it continued in that vein to the end. The scenes in the land of the dead were particularly striking; redolent of Gustave Dore’s monochrome illustrations for Dante’s inferno. And the key character in the season was Ruth Wilson’s Mrs Coulter – like Cawood, somebody seemingly in command, though in her case for selfish and occasionally downright evil ends, but who came to a degree of self-realisation and did the right thing in the end. Another satisfying conclusion.

I don’t usually shortlist third seasons but am glad to make an exception for both these two. His Dark Materials built to a great climax and I had been close to shortlisting it twice before. Indeed, I noted in my blog in December 2020 that, given its provenance as a trilogy of novels, it was probably best to leave it to the end to consider shortlisting it, which has now come to pass. In the case of Happy Valley, I would certainly have included season 1 in my top ten of 2014, but the first two seasons had already been transmitted before I started blogging in 2017, so I am delighted to be able to shortlist the third on behalf of the whole.

Something which regularly adds to the air of gloom in January is the sombre programming which marks the period around Holocaust Memorial Day. It can be unfortunately easy to note its presence without engaging too closely with it, and many of the items have been seen before, but this year it contained two outstanding new pieces, both on BBC4; one of them an extensive look at the subject from a new angle by my favourite American documentarians, the other a piece of inspired documentary minimalism – Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s The US and the Holocaust and Bianca Stigter’s Three Minutes: A Lengthening. The former was pretty much what you would expect from Burns and Novick, though no less impactful for that, and I don’t think I really need to say any more about it other than that it is automatic for the list. But the latter was a revelation.

The three minutes in question is a fragment of home movie, some of it in colour, shot in 1938 by a Jewish émigré to America, returning to his home town in Poland. It shows the Jewish community in that town, eagerly crowding around the camera and going about their daily lives. The full three minutes is shown, silently, at the start of the documentary, and for its remaining 66 minutes, you see nothing but images from those brief shots: enlarged, reversed, slowed down, every section of the frame examined for the minutest clues as to what and whom we are seeing and what the film can tell us. It is constructed like a piece of minimalist music, with constant repetition of the same material in different forms, and the more it is repeated, the more mesmerising it becomes.

It also draws you into the world of those people whose community will be destroyed in the coming years. The forensic nature of the enquiry does not lessen the emotional impact of the piece, given even greater strength by Helena Bonham-Carter’s restrained and questioning narration. For me as a career film archivist, it also spoke to many of my professional interests. The searching for clues in the background of the frames and the imperative to put names to the unidentified faces took me back to my cataloguing days. The presentation of the footage in its correct ratio and speed was also important. Digitisation was clearly vital to the manipulation of the images later in the piece, but there was no attempt to “improve” the quality of the images with the sort of software which can add frames, smooth motion and (worst of all) add colour where there is none, until near the end when a brief section was subjected to digital cleaning and Bonham-Carter asks the viewer if the process gives them any greater empathy with the people in the shot; a key claim of those, like Peter Jackson, who are fond of such manipulation. No answer is given in this film. Maybe some viewers would have said “yes”, but for me the moment begged the answer “no”, though maybe that was my own bias showing through (and I like ambiguity in documentary as well as drama, so it was well judged).

Above all, the documentary illustrates precisely how important film is as a historical record, when properly presented. I can’t think of anything, even in the complete works of Ken Burns, which makes that point more successfully and it is very gratifying to people like me who have devoted their time to ensuring its preservation. The section when all the faces are collated into one mosaic image becomes a permanent audiovisual memorial to those who probably have no gravestone.

So, four shortlisted programmes in the first month (and a bit) is a great start to the year. Maybe I’ll be making some choices at the end of it this time.

then I didn’t expect to be giving up after the customary 5 episodes I usually give to something which has clear pedigree and promise and which has received a positive welcome from sources I respect (as well as the wider critical community), but which just did not work for me. Watchmen (HBO/Sky Atlantic) suffers from the same problems I identified previously with The Handmaid’s Tale: it is so much in love with its own central concept and the visual realisation of that concept that it neglects the fundamental building blocks of plot and character development – something you can get away with in cinema, but not in an extended series. This may be because the original source material is, quite literally, two-dimensional, but the screenwriters, directors and actors are there to adapt that material for TV presentation and obviously have the skills to do so. However, the writers and directors of Watchmen seem too keen on the visuals and on drawing clever parallels with aspects of our troubled times, while the performers are hamstrung by having to wear masks for much of the time – precisely the reasons, I think, why we have recently heard criticism of superhero movies from masters like Scorsese and Coppola.

then I didn’t expect to be giving up after the customary 5 episodes I usually give to something which has clear pedigree and promise and which has received a positive welcome from sources I respect (as well as the wider critical community), but which just did not work for me. Watchmen (HBO/Sky Atlantic) suffers from the same problems I identified previously with The Handmaid’s Tale: it is so much in love with its own central concept and the visual realisation of that concept that it neglects the fundamental building blocks of plot and character development – something you can get away with in cinema, but not in an extended series. This may be because the original source material is, quite literally, two-dimensional, but the screenwriters, directors and actors are there to adapt that material for TV presentation and obviously have the skills to do so. However, the writers and directors of Watchmen seem too keen on the visuals and on drawing clever parallels with aspects of our troubled times, while the performers are hamstrung by having to wear masks for much of the time – precisely the reasons, I think, why we have recently heard criticism of superhero movies from masters like Scorsese and Coppola. Philip Pulman’s novels by the prolific and excellent Jack Thorne (and what a year he has had with The Virtues, The Accident and now this), it contains epic effects, talking animals and mystical themes, yet its characters are all-too-human. It also has one of the most arresting title sequences since The Night Manager. And it reminded me, in many aspects, of Netflix’s Stranger Things, not least the remarkable similarity in both looks and performance between Dafne Keen and Millie Bobby Brown.

Philip Pulman’s novels by the prolific and excellent Jack Thorne (and what a year he has had with The Virtues, The Accident and now this), it contains epic effects, talking animals and mystical themes, yet its characters are all-too-human. It also has one of the most arresting title sequences since The Night Manager. And it reminded me, in many aspects, of Netflix’s Stranger Things, not least the remarkable similarity in both looks and performance between Dafne Keen and Millie Bobby Brown. completely new take on the overly familiar material. It achieved its effect primarily through an impressive visual imagining of a devastated Edwardian landscape and, as it only ran to three hour-long parts, the makers were able to strike a perfect balance between the human story and the visualisation.

completely new take on the overly familiar material. It achieved its effect primarily through an impressive visual imagining of a devastated Edwardian landscape and, as it only ran to three hour-long parts, the makers were able to strike a perfect balance between the human story and the visualisation. beautifully scanned black and white photographs, the authoritative voice of Peter Coyote. But the longer it went on, the more I got the feeling that this was not the best choice of subject for such lengthy treatment. Compared to Jazz (PBS, 2001), there just wasn’t the depth of interest to be explored. Country Music also seemed to promise at the start of each episode that it would be tracing a link between the music and American social history (as Jazz had done so well), but most of what we got was just the lives and careers of the stars. As before with a Burns series, the BBC is giving us the cut down (9 hours!) version – I have usually sought out the full version (18 hours in this case) but will not be bothering this time. Maybe my problem is that it is not a style of music which interests me greatly, but I do normally expect more from Burns.

beautifully scanned black and white photographs, the authoritative voice of Peter Coyote. But the longer it went on, the more I got the feeling that this was not the best choice of subject for such lengthy treatment. Compared to Jazz (PBS, 2001), there just wasn’t the depth of interest to be explored. Country Music also seemed to promise at the start of each episode that it would be tracing a link between the music and American social history (as Jazz had done so well), but most of what we got was just the lives and careers of the stars. As before with a Burns series, the BBC is giving us the cut down (9 hours!) version – I have usually sought out the full version (18 hours in this case) but will not be bothering this time. Maybe my problem is that it is not a style of music which interests me greatly, but I do normally expect more from Burns. Netflix series Our Planet, which gave us not just spectacular sequences, but also ecological comment. Then there was Attenborough’s personal single doc on climate change for the BBC. So, Seven Worlds, One Planet (BBC1) was simply a re-hash of what we had already had and many sequences were overly familiar – not just the penguins and albatross searching for their chicks or the co-ordinated dancing birds, but even the walruses falling off cliffs which we had already seen earlier in the year. And the material on climate change became less prominent as the series progressed and seemed to have been added almost as an afterthought.

Netflix series Our Planet, which gave us not just spectacular sequences, but also ecological comment. Then there was Attenborough’s personal single doc on climate change for the BBC. So, Seven Worlds, One Planet (BBC1) was simply a re-hash of what we had already had and many sequences were overly familiar – not just the penguins and albatross searching for their chicks or the co-ordinated dancing birds, but even the walruses falling off cliffs which we had already seen earlier in the year. And the material on climate change became less prominent as the series progressed and seemed to have been added almost as an afterthought.

A new series by Ken Burns is always a major event and The Vietnam War (currently playing on Mondays on BBC4) is certainly the most significant thing he (together with his collaborator, Lynn Novick) has produced for quite some time. Any documentary series on that war was always going to attract criticism from various quarters, and, though the critical response has been overwhelmingly positive, the series does have its detractors. The tag-line “there is no single truth in war” indicates Burns and Novick’s approach, but will no doubt be regarded as a get-out clause by those with their own agendas on the subject. For me, it is one of the best things he has done and my sole regret is that the BBC is only giving us half of it – the so-called “international version”, with each episode reduced to 55 minutes – just as they did all those years back with The Civil War. The good news is that the full version will be available on DVD at the end of the month, though at a hefty price (I sense a stitch-up here).

A new series by Ken Burns is always a major event and The Vietnam War (currently playing on Mondays on BBC4) is certainly the most significant thing he (together with his collaborator, Lynn Novick) has produced for quite some time. Any documentary series on that war was always going to attract criticism from various quarters, and, though the critical response has been overwhelmingly positive, the series does have its detractors. The tag-line “there is no single truth in war” indicates Burns and Novick’s approach, but will no doubt be regarded as a get-out clause by those with their own agendas on the subject. For me, it is one of the best things he has done and my sole regret is that the BBC is only giving us half of it – the so-called “international version”, with each episode reduced to 55 minutes – just as they did all those years back with The Civil War. The good news is that the full version will be available on DVD at the end of the month, though at a hefty price (I sense a stitch-up here). The first major widescreen historical documentary series, Jeremy Issacs’ Cold War (Turner/BBC, 1998) came as something of a shock. It wasn’t just that parts of the 4:3 images were being lost – it was that their very nature seemed to be changed. According to the shorthand of the medium, widescreen images were associated with the cinema, so factual material was being made to look fictional, it seemed to me. This had already been done in the cinema itself, in films like The Unbearable Lightness of Being (Philip Kaufman, 1988), but not in documentary. Indeed, it was the rapid growth of the “cinematic” documentary (designed for cinema release or festival showcasing in the first instance, but ultimately intended for TV or home video), which normalised the practice and made it ubiquitous.

The first major widescreen historical documentary series, Jeremy Issacs’ Cold War (Turner/BBC, 1998) came as something of a shock. It wasn’t just that parts of the 4:3 images were being lost – it was that their very nature seemed to be changed. According to the shorthand of the medium, widescreen images were associated with the cinema, so factual material was being made to look fictional, it seemed to me. This had already been done in the cinema itself, in films like The Unbearable Lightness of Being (Philip Kaufman, 1988), but not in documentary. Indeed, it was the rapid growth of the “cinematic” documentary (designed for cinema release or festival showcasing in the first instance, but ultimately intended for TV or home video), which normalised the practice and made it ubiquitous. documentaries in terms of its use of TV archive material is James Lapine’s Six by Sondheim (HBO, 2013), in which a large number of interviews with the Broadway composer are intercut, all retaining their original ratios and framed in the shape of contemporary television sets, which conveys the impression of the subject’s consistent brilliance at different points in his career, without the need to signpost dates or provenance. Similarly, Andrew Jarecki’s The Jinx (HBO, 2015), uses TV archive material from the 1980s to the 2000s carefully framed within the high-definition 16:9 frame and often with “blurred” top and bottom edges to convey a constantly shifting time frame (including material from the brief hybrid 14:9 era, when that ratio was used as a compromise during the transition from 4:3 to 16:9).

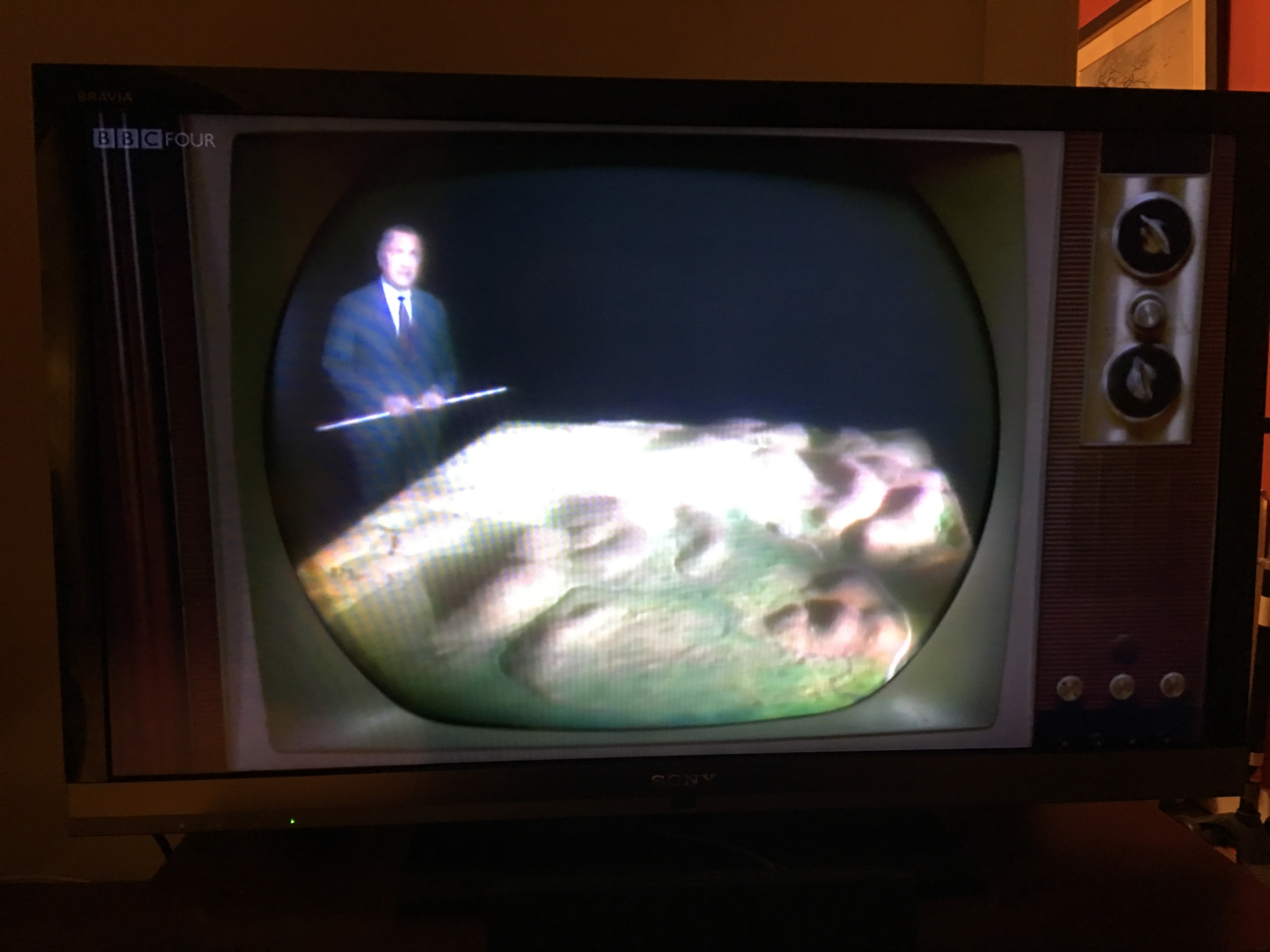

documentaries in terms of its use of TV archive material is James Lapine’s Six by Sondheim (HBO, 2013), in which a large number of interviews with the Broadway composer are intercut, all retaining their original ratios and framed in the shape of contemporary television sets, which conveys the impression of the subject’s consistent brilliance at different points in his career, without the need to signpost dates or provenance. Similarly, Andrew Jarecki’s The Jinx (HBO, 2015), uses TV archive material from the 1980s to the 2000s carefully framed within the high-definition 16:9 frame and often with “blurred” top and bottom edges to convey a constantly shifting time frame (including material from the brief hybrid 14:9 era, when that ratio was used as a compromise during the transition from 4:3 to 16:9). material. The use of period TV screens to showcase old footage is nothing new, but Burns makes dramatic use of it by filling the 16:9 screen to the very edges with the image of the 60s TV set, thus transforming your TV into one from the period, so that you experience the broadcast as it first happened.

material. The use of period TV screens to showcase old footage is nothing new, but Burns makes dramatic use of it by filling the 16:9 screen to the very edges with the image of the 60s TV set, thus transforming your TV into one from the period, so that you experience the broadcast as it first happened.