The final stage of my classical CD collection listening-while-driving marathon was (apart from a little Weber and a couple of Zs to complete the journey) my extensive Wagner collection. My very extensive Wagner collection. So extensive that I needed to space it out and intersperse it with some of the classical compilation albums I have as well as revisiting some of the things I had already heard and completing the alphabet before the fat lady sang for the last time. It’s not that he wrote that many different works (11 operas in my collection, plus the one song-cycle and a couple of orchestral pieces) – it’s that I have so many different versions of them and didn’t want to hear them back-to-back. You need to understand that Wagner has been something of an obsession of mine since I first got into “serious” music. The large majority of my visits to opera houses have been for Wagner works.

Anyway, as I said, my Wagner CD collection takes up the most space on my shelves. I have just the one copy each of Rienzi, The Flying Dutchman and Tannhauser, then two Lohengrins, three Tristans, three Meistersingers, four Ring Cycles and four Parsifals. And, if you think that is over-the-top, I also have DVD or blu-ray productions of Rienzi, Tannhauser (2 versions), Lohengrin (3, including the brilliant Werner Herzog Bayreuth production), Tristan (3), Die Meistersinger (4), Parsifal (3) and no fewer than 5 complete Ring Cycles. Thank goodness I can’t watch DVDs in my car!

One of the reasons I revere Wagner so highly is that his achievement is far more than a musical one. Although I obviously loved listening to so much glorious and familiar music again (and again, and again) this time I found myself concentrating particularly on the words and the drama while listening. Wagner’s reputation as an artist is based on his musical achievements, but his skill as a dramatist should not be underrated. It is so advanced that he would surely have been a film auteur if he had been born a century later. Listening in the car, paradoxically, allowed me to focus on this. When you watch a production in the opera house or on DVD, you take the drama for granted and are caught up in it, especially if it is being interpreted by an outstanding stage director and the best singer/actors (and I prefer singers who throw themselves into the roles to those with outstanding voices who just stand there singing). This applies particularly to The Ring, but I will leave that until a later blog and concentrate here on the other works.

Rienzi is a bit of a strange one. It the last of Wagner’s earliest three operas, but the first that is in any way worth listening to. On the other hand, it does not belong in the same rank as the next three, which themselves are harbingers of his later, mature masterpieces. He took a comparatively long time to find his true level, but the journey there was pretty splendid in itself. Complete recordings of Rienzi have been rare and the version I have, conducted by Hollreiser on EMI, was among the first to become available. Productions are also rare and the only one I saw in a theatre was the ENO staging in 1983. It actually lends itself well to modern interpretation, though few directors can resist visual references to Italian fascism. That was certainly true of the ENO production, which used film and architectural grandeur to great effect. Indeed, the fascistic statue which dominated the stage in Act 4 remains the only instance when I have heard a set design get a round of applause as the curtain rose. The production from the Deutsche Oper, which I have on blu-ray is very similar and also uses fascistic-style propaganda film. The music of Rienzi has some splendid moments, especially the choruses, but also some longueurs – the drama often drags somewhat and does require startling visuals to be of interest.

After which, of course, he really got going. The next three works are usually grouped together, mainly because they are operas, with arias, duets and choruses, rather than music-dramas, as he preferred to describe his major works. Interestingly, Wagner actually revisited some of the themes and concerns of these three works in his three later non-Ring music dramas, and even in the same order. Thus, the idea of redemption through love-in-death which features in The Flying Dutchman is later given considerably more intensity in Tristan and Isolde, which similarly features maritime scenes. In Tannhauser, Wagner explored the position of the artist (and specifically the musical artist) in society and enlarged on his theories of the artistic process and the conflict between innovation and tradition in The Mastersingers of Nuremberg, both operas also featuring song contests. Finally, the use of the grail legends as source material for Lohengrin was repeated with Parsifal, which is basically a prequel for the earlier work (and what a shame it didn’t become a tetralogy like The Ring – there’s certainly enough backstory in the expository parts of Parsifal).

My CD copy of The Flying Dutchman is the classic Klemperer recording on EMI. The best production I ever saw on stage was the 1978 production by Harry Kupfer at Bayreuth, in which the entire story was presented as a figment of Senta’s febrile imagination. This made perfect sense both dramatically and because she has the most intense music in the opera. Similarly, the CD version I have of Tannhauser is Solti’s definitive version on Decca, with Rene Kollo outstanding in the title role, while my favourite stage production is also a revolutionary Bayreuth production by Gotz Friedrich. This caused quite a stir when it premiered in 1972, mainly because of the “workers’ chorus” which brought it to a conclusion. I saw it the following year, on my first visit to Bayreuth, by which time it had been toned down a little, and found it extremely powerful. Fortunately I also have both these landmark productions on DVD.

The Claudio Abbado version of Lohengrin, with Placido Domingo in the title role, is pretty good, but I prefer the older DG set by Rafael Kubelik, with James King. My favourite production on DVD has to be Werner Herzog’s Bayreuth staging, with its beautiful tableaux reminiscent of paintings by Caspar David Friedrich. Herzog also later made a documentary film about the Bayreuth Festival, The Transformation of the World into Music, which was intended for showing on German TV as an introduction to screenings of Bayreuth productions, and is well worth a watch.

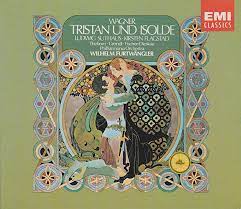

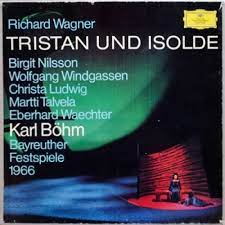

By the time he got to Tristan und Isolde (over half way through the composition of The Ring) Wagner had long since moved from composing operas to creating “music dramas”. The greatest performances of his mature works are those which find the best balance between the music and the drama. However, my two favourite recordings/performances of Tristan are at either end of the spectrum. The 1952 Furtwangler recording (on EMI, in mono) is Tristan as music; the live 1966 Bayreuth recording (on DG) by Karl Bohm is Tristan as drama. You may think that listening while driving would favour the former approach., but, as I indicated earlier, that is not the case; and it is especially not the case with Tristan, where the action is fairly static and the drama comes from the intensity of the protagonists’ emotions.

The Furtwangler performance is intensely slow and beautiful, especially in the love duet in the second act (Hans-Jurgen Syberberg used the recording to tremendous effect in his film about Ludwig II) and, of course, it has the legendary Kirsten Flagstad giving probably her greatest performance as Isolde. The age of the recording (it is older than me!) does not count against it at all. The complete timing of this expansive recording is 256 minutes. Bohm’s urgent performance comes in at 37 mins shorter and fits neatly on 3 CDs (one per act). It is the best and most dramatic performance because it is live and because it features the two greatest Wagner “performers” (as opposed to singers), Wolfgang Windgassen and Birgit Nilsson, in the title roles. I’d go further – it is one of my favourite recordings of anything. Windgassen is simply astonishing in Act 3 – his intense commitment to the role is complete and sometimes he even seems to spit out his lines. Which of the two recordings ultimately moves me the most? With this work it is impossible to say, because both approaches are valid – that’s the beauty of it.

A good singer/actor in the role of Hans Sachs is vital to the success of any production or recording of the Mastersingers of Nuremberg. On stage, my favourite interpreter was always the wonderful Norman Bailey, whom I saw sing the role many times. He also features on two of the three CD sets of the work which I have: with Goodall in the live ENO production (on Chandos, in English) and in Solti’s studio production (on Decca, in German). And yet, my favourite set is Karajan’s on EMI. Theo Adam may not quite match Bailey, but is, nevertheless a splendid Sachs, while the rest of the cast is superb – especially Geraint Evans as Beckmesser and Peter Schreier as David, both of whom add to the comic aspects of the piece.

Other Wagner works vie for the title of my favourite, but, when I am actually listening to it, especially the phenomenal third Act, I always find myself thinking: “did he really write anything better?”. And, for me, the crux of that heavenly act is the composition of the prize song, in which conversational dialogue is accompanied by a constant flow of sublime music. And, in that scene, Wagner put into Sachs’s mouth his own feelings on innovation and tradition in art, illustrated by the development of Stolzing’s song. Of course, Wagner was himself a great musical innovator, especially in Tristan, which was the work which preceded the Mastersingers. But he did not espouse experiment for its own sake – it needed to grow organically from existing forms and the “rules” were there to provide a context within which they could be successfully broken. This scene rarely fails to get me, whatever the context of the production, and was a highlight of the Barrie Kosky staging (which I reviewed in my blog of August 26th 2018), in which both the characters were dressed to represent Wagner at different stages of his career. After I had finished my classical collection, my listening-while-driving moved on to some of my favourite rock and pop artists and I found Wagner’s ideas about innovation in music very apposite in assessing what I was hearing. I will return to that in the future.

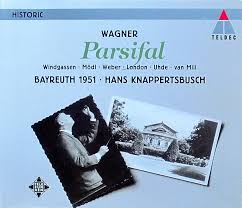

My collection of recordings of Wagner’s final work, Parsifal, like that of Tristan, encompasses the slow and the fast, the old and the less old and the live and the studio. “Live”, in the context of Parsifal recordings, usually means Bayreuth and, as the work was specifically created by Wagner for the unique acoustic and orchestral layout of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, these recordings must be regarded as the most authentic. Probably my favourite is the 1951 recording by Knappertbusch (which can now be picked up on the bargain Naxos label), with a fresh young Windgassen in the title role and Martha Modl superb as Kundry. Like Furtwangler’s Tristan, it is slow (total run time 272 minutes) and intensely beautiful. By contrast, the live Bayreuth recording from Pierre Boulez on DG comes in at a brisk 219 minutes (close to an hour faster for exactly the same music!). It also includes a wonderful Kundry in Gwyneth Jones, who embodies the difference between the singer/actor and the singer with her blood-curdling screams and groans, which are acted rather than sung.

My favourite experience of a staged production of Parsifal has to be my first visit to Bayreuth in 1973, when I was fortunate to get a ticket for one of the performances in the final year of Weiland Wagner’s spare staging which revolutionised Wagner production when the festival re-opened for the first time after the war, and which was the production from which the Knappertsbusch recording mentioned above was taken. Parsifal lends itself well to spare stagings rather than complex ones, as one can concentrate on the music rather than the action (of which there is not a great deal). Having said that, though, I am particularly fond of Nicholas Lenhoff’s production, which I have on DVD and saw a version of at English National Opera.

Anyway, as I said above, I will leave The Ring for a future blog, but it will be back to TV next time out. My driving marathons continue to this day and, after finishing my classical collection, I moved on to some classic rock and pop and will be blogging a few lists on that experience, as well as the classical music lists I promised.

production of Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg. Not only was this a welcome opportunity to experience a very new and exciting production, but it is available at a rock-bottom bargain price (still under £15 last time I looked) and, when you consider that a ticket to see it in the Festspielhaus, if you were lucky enough to get one, would set you back upwards of two hundred (plus, of course, the cost of getting and staying there) the importance of such recordings being released is clear. Incidentally, though I hate to hear productions or performances being booed, the astronomical cost of attendance does make it a little bit understandable if someone feels they have been short changed.

production of Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg. Not only was this a welcome opportunity to experience a very new and exciting production, but it is available at a rock-bottom bargain price (still under £15 last time I looked) and, when you consider that a ticket to see it in the Festspielhaus, if you were lucky enough to get one, would set you back upwards of two hundred (plus, of course, the cost of getting and staying there) the importance of such recordings being released is clear. Incidentally, though I hate to hear productions or performances being booed, the astronomical cost of attendance does make it a little bit understandable if someone feels they have been short changed. guests are given roles while other characters emerge (many in full reformation-era costumes, based on Durer) from his piano. Wagner himself plays Sachs (of course), though Walther and David clearly also represent himself at different stages of his artistic development, which fits perfectly with the theories of art he is exploring, as well as his own vanity. Cosima plays Eva, while her father, Franz Liszt, plays … her father. The Jewish conductor, Hermann Levi, is cajoled into the role of the comic villain Beckmesser, much as he had to endure Wagner’s antisemitism in order to be an important part of his artistic endeavour. The effect of this is to allow the director to explore issues raised by and concerning the work while not, as often happens with high-concept productions, working against what the music and the words are telling us – everything fits perfectly. The singers are historic characters playing operatic characters and are thus able to play those (operatic) characters much as they may in a conventional production.

guests are given roles while other characters emerge (many in full reformation-era costumes, based on Durer) from his piano. Wagner himself plays Sachs (of course), though Walther and David clearly also represent himself at different stages of his artistic development, which fits perfectly with the theories of art he is exploring, as well as his own vanity. Cosima plays Eva, while her father, Franz Liszt, plays … her father. The Jewish conductor, Hermann Levi, is cajoled into the role of the comic villain Beckmesser, much as he had to endure Wagner’s antisemitism in order to be an important part of his artistic endeavour. The effect of this is to allow the director to explore issues raised by and concerning the work while not, as often happens with high-concept productions, working against what the music and the words are telling us – everything fits perfectly. The singers are historic characters playing operatic characters and are thus able to play those (operatic) characters much as they may in a conventional production.

operatic creation in the 20thcentury, and the 2012 touring revival, which I saw at the Barbican, was essentially the same thing as first seen in 1976. That production (recorded in Paris and released by Opus Arte) has been available on Blu-ray since late 2016 but somehow the sophisticated algorithms employed by Amazon and others failed to notify me, despite the internet knowing full well that I am a big Philip Glass fan. I had assumed it would remain an unforgettable theatrical experience only and was delighted to find otherwise.

operatic creation in the 20thcentury, and the 2012 touring revival, which I saw at the Barbican, was essentially the same thing as first seen in 1976. That production (recorded in Paris and released by Opus Arte) has been available on Blu-ray since late 2016 but somehow the sophisticated algorithms employed by Amazon and others failed to notify me, despite the internet knowing full well that I am a big Philip Glass fan. I had assumed it would remain an unforgettable theatrical experience only and was delighted to find otherwise.