Fifteen months ago, at the end of July last year, I wrote a blog about how I had been working my way through my classical CD collection on my regular drives to the Sussex coast to look after my elderly parents following my father’s fall, hospitalisation and rehabilitation. Not too long after he got home in the late summer, my father fell again and the cycle repeated itself, though at greater length this time. He was back home by late Autumn and in time for a restricted celebration of their 75th wedding anniversary in December. But in early February his third fall put him back in hospital and there would be no coming home this time. A care home was the only option and he was there until he passed away in August at the grand age of 96. All of this necessitated constant visits from myself, both to organise my father’s care and to look after my mother and to run their house and finances. I got to know the route intimately and observing the gradual seasonal changes to the countryside over the course of more than a year was a great solace. So of course, was the music. In my previous blog I described how I got through the composers beginning with A and B while travelling from A to B. Since then I have reached the end of the P section and further driving to the west country to take our daughter to her new college has offered added listening time, as has the return of football. So, here are some thoughts on composers and recordings in my collection from C to P.

Late summer 2020 brought the first changes to my drive since I began the regular route. Lockdown had eased, so there was more traffic about, plus the increase in agricultural vehicles on the country roads which that time of year brings. This gave me even more time to realise, as I had not fully done before, what a wonderful composer Chopin is: his second set of etudes (Op. 25), played by Pollini, are a delight and I prefer them to the more famous ones in the earlier dozen. The season also brought the renaissance glories of Desprez (or Josquin, though I have filed him under D) and Dufay – both composers of the first rank. I recently bought a bargain set of 34 CDs on Warner Classics called Josquin and the Franco-Flemish School, so I was able to revisit their world and that of a large number of their contemporaries, many new to me, this summer as well as last. It was good to have their tranquil company around the time of my father’s death.

My Desprez and Dufay collections are separated by just one disc of Dohnanyi’s lovely string quartets and then it was on to Dvorak. The DG Kubelik set I mentioned in my earlier blog gave me the opportunity to hear a full cycle of his symphonies for the first time (conducted by his best interpreter) and I was struck by how you can discern a definite progression by listening to them in order. Most composers of nine or more symphonies have their most outstanding works scattered amongst the set (think of Beethoven’s 3rd, 5th and 9th), but Dvorak’s just get steadily better. The earliest ones are very much influenced by Beethoven, but his own voice begins to emerge around the 6th and is fully formed by the 8th. But the best of Dvorak are his string quartets, particularly the “American”, which contains four equally striking and memorable movements. This got me thinking about the string quartet as a musical form, as it has become one of my very favourites and has proved a versatile platform for a good many composers from the 18th century to the present day. I had already enjoyed all of Beethoven’s remarkable quartets and Debussy’s single, but wonderful, attempt at the form and had Cesar Franck’s even better one about to come along a little further down the road. String quartets may prove a good subject for a separate blog one day and I’ll certainly be coming back to them several times before this one is out.

By the time Autumn arrived, I had moved through E and F and was on to one of my largest composer collections (and certainly my largest by a living composer): Philip Glass. I have to admit, I was a bit daunted by the prospect of listening to so much of his music at one time, but I was amazed at how much I appreciated the variety of his output. The standard criticism of Glass is that his stuff “all sounds the same”, but I guess that is true of many great composers who establish their own distinctive sound (Mozart comes to mind). It’s just that with Glass, the variations are very subtle, but they are there and each piece has its own character. And there is such a wide range of forms – symphonies, concertos, quartets (brilliant ones!), operas, ballets, electronica, song cycles, solo piano, tone poems and, of course, all those wonderful film scores: the “qatsi” ones stand out because the music was an equal partner with the visuals in those films, but I think his score for Paul Schrader’s Mishima: a Life in Four Chapters is arguably the greatest film score of all in terms of its expressiveness and flexibility (I can feel another separate blog coming on) and it also supplied the themes for his finest string quartet. I have already blogged, a couple of years back, about his masterpiece Einstein on the Beach, and, thanks to ENO, had seen Akhnaten and Orphee on stage in the last few years. I’d not been to an opera since the first lockdown, but with Satyagraha re-opening the Coliseum recently, I couldn’t wait to get back and it was fantastic (both production and performance). One last thing about Philip Glass – it is wonderful music for driving to but is maybe just too good. Many times, I found myself going way too fast without realising I was doing it. The momentum of his music takes over and not just in the obvious pieces like The Grid from Koyaanisqasi, but throughout his oevre. Beware!

Before winter 2020/1 set in and as the leaves fell on my journeys, I reached the end of G and, as with my previous negative re-assessments of most of Brahms and Bruckner (as described in last year’s blog), I determined that the works of Edvard Grieg are unlikely to be bothering me again. But winter brought Handel and Haydn to lighten the darker drives.

It struck me that Handel is probably the composer to whom one could most readily compare Glass, both in terms of the range of their respective outputs and, indeed, the musical construction of the pieces themselves. Handel’s music is littered with what I would (crudely) call “diddle-daddle, diddle-daddle” moments (think of the Arrival of the Queen of Sheba from Solomon), while Glass’ favourite equivalent would be “diddly-daddly, diddly-daddly” (I think real music experts refer to these as arpeggios, but I know what I‘m talking about, even if you don’t). Handel is also a key composer in the original instruments debate. I have two versions of The Messiah. I love and would not be without the Charles Mackerras recording on EMI, but that may be mainly for the presence of Janet Baker and I ultimately prefer Paul McCreesh’s version with the Gabrieli Consort on DG Archiv. And both Gardiner and Pinnock present marvellous recordings of the Fireworks and Water Music suites.

Haydn’s symphonies are really boring, I now realise. Only number 104 (104!) is any good and that is his last one. Part of the problem is that he rather overdoes it with the minuets, possibly the most tedious and predictable musical form of all and one which only really found its true level with The Wombles in the 1970s and their assertion that forgetting to be minuetting was letting the other minuetters down. His string quartets, on the other hand, are outstanding. There are lots of them and they are pretty much all excellent. Even minuets have a certain charm when played by a string quartet. I should also mention that, having used the term “Four Seasons” in my blog title and having not reached R or V yet, the only work called The (Four) Seasons I have listened to these past four seasons is the oratorio by Haydn.

But, before we say goodbye to H and winter, I should mention one particularly serendipitous moment while I was driving along listening to film music by Bernard Herrmann and a particularly severe downpour forced me to turn my wipers to maximum speed just as the Psycho Suite came on. Perfect!

I, J, K and L take up a mere 3 inches on my CD shelves, though it is only really J and L – I have no Is or Ks (not even Ives). I also really need more than one disc of each of Ligeti and Liszt, though one of Leoncavallo is perfectly adequate and you can guess the work. My 2-disc DG Archiv set of Orlando di Lassus was also not enough but has since been supplemented by a larger number of his works in the Josquin set I mentioned, allowing me a much greater appreciation of his glorious music.

Early spring brought me to another large collection and the composer who is probably my second favourite of all: Gustav Mahler. It isn’t that there are that many works – nine and a half symphonies, five orchestral song cycles and an early cantata – but they are big works and I have multiple copies of them all. The Kubelik and Haitink symphony cycles which I have are a great contrast, but are both very good, though the symphonic recording I treasure most is Horenstein’s 4th with the LPO on the budget Classics for Pleasure label. This is not so much because it is an outstanding performance (though it certainly is that) as because it was my introduction to Mahler at a college Music Club gathering 50 years ago this autumn. I borrowed the disc from a good friend for the Christmas holiday and never looked back. Recently I have been attempting to hear all the symphonies again in the concert hall and, before lockdown struck, had managed all but the 7th. A Proms performance of the 3rd by the Boston Symphony a few years back, together with one on the Berlin Phil’s digital platform, helped finally convince me that it is my favourite of his works (supplanting the 2nd). The way the final three movements fit together, from the gravity of “Oh, Mensch”, through the joy of “Bimm, Bamm” to the serenity and climactic affirmation of the gorgeous finale is just transformative. I have four recordings and loved listening to them all, especially on the longer journeys to the west country, which began for me (and my wife, Dejanka) when our daughter, Hanna, began college there at this particular time. Rating Mahler’s symphonies is a fairly futile exercise, though. I have looked at a number of lists online, some of them headed “from best to worst”, as though the term “worst” could possibly be applied to a Mahler symphony. They are all outstanding and my own attempts to put them in an order of preference failed miserably. I mean, how could I possibly put the first symphony last, as I ended up doing on every attempt? At the same time as I listened to his music, I read a biography of Mahler by Michael Kennedy, which had been sitting on my shelves for some years and which really enhanced the experience.

Before continuing with the Ms, which is another of those letters, like B and S, with a large number of major composers, I realised that I would need to buy a set of Mendelssohn string quartets if I was to continue my exploration of that form. And I’m very glad I did, because I had previously thought of him as a composer of bright and joyful music, but the quartets showed me that he also had an introspective side which I had not heard before.

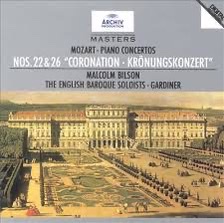

And, as spring moved into summer, I was happily accompanied by two of the all-time greatest: Claudio Monteverdi and Wolfgang “Amadeus” Mozart. My favourite Mozart symphony is undoubtedly the Prague (no.38), mainly because it has three gloriously memorable and perfectly balanced movements, which also means that, unlike all the others, it has NO minuet. Young wombles may have been told that “if you minuetto/allegretto you will live to be old”, but that sadly did not apply to Mr Minuetting Mozart himself. Or, to quote one of my favourite Tom Lehrer lines, “it’s a sobering thought that when Mozart was my age, he’d been dead for five years”. Even so, there is just such a wide variety of wonderful and inspiring stuff in Mozart’s catalogue, the very best of which, for me, are his piano concertos, especially when played on an 18th century piano by Malcolm Bilson accompanied by the English Baroque Soloists under Gardiner. The set of six string quartets, dedicated to Haydn, aren’t bad either.

By early May, I had reached Mozart’s choral works and enjoyed another of those serendipitous moments when I drove home in a totally euphoric state after Brentford’s win in the play-off final at Wembley. Not only was it one of the first games it had been possible to attend after lockdown, but our victory got us back to the top division for the first time in 74 years. And the piece I put into my car music system was Exsultate, Jubilate. Exult! Rejoice! I listened to it twice. It was a perfect moment.

Then it was on to Mozart’s operas. There has been plenty of debate about which of Mozart’s four great operas is the best and I certainly have my own favourite, which is the Magic Flute. The main reason is, of course, the music – it just has great number after great number, from start to finish. Don Giovanni also has its fair share of stunners, but the other two are nowhere near. I have three other reasons for favouring Zauberflote: its mythic setting; the fact that it is in German, which, for me, is the best language for opera; and the fact that it dispenses with recitative (which drives me spare) in favour of spoken dialogue. I was also reminded that I had the wonderful duet “Bei Mannern welche Liebe fuhlen” played at our wedding. I have three DVD/Blu-ray versions of the opera (including Bergman’s film) and two CD sets. Bohm is great, but Gardiner, once again, is best.

I was well into summer by the time I reached the end of M, which brought me to best of all Russian operas – Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. There were two versions (1869 and 1872) and the Gergiev set on Philips has both, so I got to enjoy it twice.

I’ve got a lot of CDs of Michael Nyman’s considerable output and listening to them all together emphasised the range and quality of his work, which basically falls into two categories – that written for the Michael Nyman Band and that written for more traditional ensembles like orchestras and string quartets. The numerous film scores can also be divided like that, though the division tends also to reflect his work with Peter Greenaway and the later soundtracks. Listening to much of it brought back memories of performances I attended in the nineties. Two in particular stand out: a Festival Hall premier of the Upside- Down Violin, during which a young boy in arab dress started dancing on his seat a few rows in front of me – his parents tried to stop him, but everybody said to let him carry on, as it was very much in the spirit of the occasion. Then there was a rainy summer evening in Greenwich Park with my wife, soon after we met. I’m a really big Nyman fan, even though he is a QPR supporter.

O and P included two 20th century stylists. Firstly Carl Orff, whose Schoolwork provided perfect driving music for many hours and a reminder of one of the most perfect choices of music for a film: Terrence Malick’s use of it in Badlands (1973), exploiting its simultaneously naïve and sinister qualities. I can also never listen to Carmina Burana without remembering a Prom performance I attended in the mid seventies: it was a hot and humid August night and the heavy lighting required for colour video in those days (it was being recorded for broadcast) made the Albert Hall a cauldron – so much so that the bass Thomas Allen fainted during his first solo and knocked over the cello section in falling backwards. Anyway, a replacement walked out soon after and had a quick word with conductor Andre Previn. The next day’s papers revealed he was a music student who had been in the audience and volunteered to sing because he knew the part. Alas, this was not the romantic start of a big career – he had his moment in the spotlight and then was never heard of again. Then, when I reached Arvo Part, I was able to supplement my listening with reading (as I previously had with Mahler), using a book of conversations with the composer which my wife kindly gave me for Christmas last year.

O and P also brought glorious music by two masters from either end of the Renaissance period: Ockeghem (also featured in my Josquin set) and the divine Palestrina. By another quirk of the alphabet, Palestrina was immediately followed by the opera about him by Pfitzner. For me, Palestrina is one of the two greatest Italian composers, together with Monteverdi. Another great Italian, Puccini, was to finish off the listening marathon I am describing here. I would rate him the greatest Italian composer since Vivaldi and my collection of his operas includes a number of performances by the greatest Italian opera singer of all – Luciano Pavarotti.

Anyway, I’m still driving and listening just as much, especially with football back and Premier League grounds to visit, but I will return to that in time and will then blog some music lists. But next time, and after a long absence, it will be back to TV.