It is precisely a year since my last blog post, which I guess makes this both my first and last blog of 2025. Apart from the number 5 at the end of the date, that was also precisely the same sentence as began my last blog, posted on 31st December 2024. My second sentence last year was “It’s not a year I will regret seeing the back of”. A lot of people doing end-of-year summaries seem to be saying that this year, mostly because of political developments, but not me. History moves on and is rarely less than fascinating whatever happens, but personal loss hits harder. However, this year has been one of consolidation, acceptance and renewal for me. While not a day goes by without me thinking about Dejanka and remembering our former life, a new life pattern has emerged and I will consider what it means for my engagement with TV and this blog in due course. A big part of that pattern is my regular days, theatre trips and occasional weekends with our daughter Hanna, who is now well settled in her supported-living house. I see her every Wednesday to take her for pizza (her favourite) and then to the choir for the learning disabled, Electric Umbrella, which she loves. It was a big year for them, appearing on Britain’s Got Talent and various other public concerts, mostly in Watford.

Looking back through my 2025 diary, my concert and opera-going (particularly to the Wigmore Hall, where any appearance by the wonderful Chiaroscuro Quartet is a must), theatre and comedy shows (including Bill Bailey and, my favourite, Stewart Lee), football and cricket attendance and overseas travel have all increased substantially. Indeed, some of the travel I enjoyed was linked to concert or opera attendance, most notably my trip in August to Bayreuth, where I hadn’t been since the 1970s, but, having got lucky in the ballot for tickets back in December last year, a place I was more than delighted to reacquaint myself with, particularly for the outstanding performance of Tristan conducted by Bychkov. Barrie Kosky’s WaIkure at Covent Garden (which I saw twice!) was another standout Wagner moment of my musical year – a brilliant production wonderfully performed. The climactic Magic Fire was not only stunning to look at and listen to – you could feel the heat, even in the balcony. With my ticket for the upcoming Siegfried booked, 2026, the 150th anniversary year of the first Ring, is likely to provide more.

Other travel involved 10 days in the hot sun of Montenegro with Hanna and a few days in Gent in autumn, built around a Philip Glass/Michael Nyman concert. I also did a lot more walking this year, culminating in a two-day epic hike along the Grand Union Canal in September. There is a sign on one of the bridges over the canal at Berkhamsted saying “Brentford, 33 miles” and I always thought to myself how good it would be to walk to a home game one day. Then I got into an exchange on the Bees online fans’ forum which ended with a pledge to do it for the 8pm kick off against Chelsea. At my age, there was no way I was doing it in a day, but with a conveniently sited Premier Inn at Rickmansworth, just off the towpath, I was able to complete it in two days without leaving the canal-side until I got to Brentford. It was a glorious experience which I hope to repeat, and maybe blog about, some time. In fact, travel, walking, music and sport could all be great blog subjects for the future.

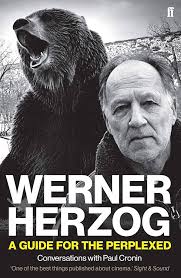

As could my continuing and systematic trawl through my DVD/Blu-ray collection, which this year encompassed the end of my post-war Italian collection (helped by some excellent releases of Visconti restorations) and the beginning of my German one. 26 films by Fassbinder and even more by Werner Herzog so far. I like to combine this with catching up on some of the film books which have stood largely unread on my shelves for many years. I have worked my way through Herzog’s filmography while reading the weighty Werner Herzog – A Guide for the Perplexed (Faber & Faber 2014), in which he talks about all his films in chronological order, so reading and viewing can proceed together in an orderly manner, giving an excellent overview of his entire career. I not only watched my existing collection of his works, but managed to fill a few gaps at the same time. For me, Herzog is the greatest living film director and I’m very much looking forward to his latest, Bucking Fastard, in the coming year.

Which brings me, finally, to the year on TV and the question I must ask myself is: did all this activity mean I had less time for TV watching, or was it simply a case of my not finding that much worth watching this year? In my blog a year ago, I speculated that, as well as there being just too much to keep up with, I was also getting out of touch with changing styles, references and sensibilities, both of which made the idea of presenting a “top ten” somewhat redundant. I guess I was doing my best to avoid falling into the “things ain’t what they used to be” mentality, which I abhor, but this year it is pretty unavoidable.

So, I will offer you not a ten best of the year, but just a list of things that I particularly enjoyed or was engaged by. There are only eight of them, and not many of them are 2025 originals, but the medium still has the capability occasionally to astonish, delight and invigorate. It is also at a delicate point, with public service broadcasting at a crossroads and streaming services beginning to repeat themselves.

The Assembly (ITV) was another breakthrough in the representation of learning-disabled people on television, but it was also a very good interview show and I felt I learned a lot more about the likes of Gary Lineker, David Tennant and (especially) Danny Dyer than I would have from a conventional chat show. The interviewers were given plenty of time to compose their questions and to express themselves, with some revelatory and moving results. The pilot (based on a French format) was actually on the BBC, but they apparently decided they could not afford the series (of four) and I will come back to that. If it was not for the show which everybody agrees was the best, The Assembly would have been my pick of the year.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Amazon/BBC1) was an outstanding Australian drama series set across different time periods, but focussed mainly on the experiences of prisoners of war at the hands of the Japanese in World War II and it was the intensity of these scenes which gave the series its tremendous emotional power.

Mo, series 2 (Netflix) continued the story of a Palestinian immigrant living in America which I had already put in my top ten a couple of years ago, but which continued to improve and became an important statement in the light of events in both the United States and Gaza this year.

Last One Laughing (Amazon Prime) gave me the most laughs this year, especially when Bob Mortimer was involved. Comedy is the area where I am most out of synch with modern sensibilities. Sketch comedy has all but disappeared (and Mitchell and Webb’s attempt to revive it was only intermittently successful), while I find most sitcoms either brainless or mystifying. Most of the comedy I watch nowadays is long-standing panel shows.

Blue Lights, season 3 (BBC1), saw the best cop show of two years ago back to its very best after a disappointing second season last year. Some great tension and set-piece scenes, plus well-drawn (and acted) characters.

South Park (Paramount) has always been, for me, the best American animated comedy, notwithstanding The Simpsons, Family Guy or Bojack Horseman. This year it showed why with its fearless and hysterically funny assault on the Trump administration.

Mr Scorsese (Apple) was a definitive five-part documentary about the significance of the great director’s career. It’ll be a while before I get to my considerable collection of Scorsese films on DVD and Blu-ray, but, when I do, I think I will need to revisit this series for essential context.

Which brings us, finally and inevitably, to Adolescence (Netflix) – everybody’s pick for best of the year. Sometimes a drama series will win that accolade for the impact it has, sometimes for the innovative method of its construction and sometimes for the quality of the acting performances. Rarely do we see something which reaches the highest levels in all three areas at once, but Adolescence was that. In his Guardian article on why it topped their “50 best” list for the year, Stuart Heritage said that, in all his time as a critic, he had never before seen something he would describe as genuinely perfect on all levels (although there were some minor continuity errors which were retained when the rest of the episode take was excellent). I go back a little further than him and can think of a few, but Adolescence is certainly up there with the all-time best dramas.

Of course, I did watch other TV this year, but saw nothing else I would include on my list. I was looking forward to the return of The Sandman (Netflix), but gave up part of the way through the third episode when it became clear that it had nothing more to offer than spectacle this time around (and I’m hoping that won’t apply to Stranger Things as well, but so far it doesn’t look good). I wish I had done the same with This City is Ours (BBC1), but it gripped until the final 10 minutes, when the resolution it was crying out for was denied us in favour of scene setting for the next season, which I will not be joining them for.

Having given you a top ten for so many years and now just a personal list of favourites, there is one further note of comparison I need to make. My previous lists have always contained a substantial number of programmes, sometimes a majority, from the BBC. This year I have chosen just one BBC-made programme and that is a drama in its third season. The poverty of the current slate of BBC TV offerings is a matter of despair for me. People who have worked for and love the BBC are often its fiercest critics because they know what it is capable of and are saddened when it falls short. For me there are two programmes emblematic of its malaise – the execrable Mrs Brown’s Boys and the populist former-ITV game show Gladiators, which didn’t deserve revival from a commercial channel, let alone our primary public service broadcaster. Both were part of a miserable Christmas Day schedule on BBC1, which was total garbage from beginning to end. An organisation which cannot find the money for an outstanding programme like The Assembly, but is prepared to splash it on Mrs Brown’s Boys, Gladiators and many more sub-standard offerings has lost its way as a public service, at least in terms of its TV output. My only hope is that the deleterious effect on programming policy is down to the outgoing Director General, the worst in my long experience as a viewer and chronicler of British television, whose hopeless efforts as editor-in-chief have brought the BBC to a point of crisis. The Corporation now needs a respected broadcaster – someone of the stature of a John Simpson – to lead it through what will be a crucial period in its long and distinguished history.

As for my blogs, I think my way ahead is now clear and has, for me, emerged in the writing of this one. I think I started TV For Keeps as a way of continuing informally what I had been doing professionally for the previous four decades. That is no longer necessary or possible for me. I’ll keep the blog title (why not?) but comments on current TV output and issues will become even more “occasional”.

Let’s see what the New Year brings – have a happy one.