A few months back, I posted a blog in which I argued the merits of telling a story visually rather than verbally (Better Left Unsaid, 31st May) using examples of some recently transmitted programmes. Without in any way invalidating those arguments, a number of recent new series have prompted me to examine the other side of the same coin: effective drama and dramatic comedies which prioritise dialogue over visuals. Of course, for these to work well they still require subtle visual flair and directorial quality and they, too, need to avoid expository dialogue as much as possible.

To start with the two most obviously “wordy” series: State of the Union (BBC2/BBC i-Player) was a series of 10 ten-minute two-handers, always set in the same pub as the two protagonists (played by Rosamund Pike and Chris O’Dowd) met up in advance of their regular weekly marriage counselling sessions. The credits for such a modest scenario were pretty striking – as well as the two excellent actors, the scripts were by Nick Hornby and the direction by Stephen Frears – which is why it worked so well. It was very much in the tradition of pieces like Hugo Blick and Rob Brydon’s Marion and Geoff (BBC: 2000-2003) or Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads (BBC: 1988, 1998). The details of the characters’ lives emerged gradually and as much by implication as by direct statement. This requires clever writing, great acting skills and subtle direction – Frears highlighted the more serious moments with the minutest of camera movements. Another outstanding two-hander, Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre (1981), is a valuable reference-point. Each episode included the week number (Week 1, Week 2 etc) in its title, so I watched them a week apart, not in twos, as they were transmitted, or by bingeing the whole 100 minutes on i-Player, as I’m sure many did, and I somehow think that was right. I imagine it will be back for another season and could well run and run.

in the tradition of pieces like Hugo Blick and Rob Brydon’s Marion and Geoff (BBC: 2000-2003) or Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads (BBC: 1988, 1998). The details of the characters’ lives emerged gradually and as much by implication as by direct statement. This requires clever writing, great acting skills and subtle direction – Frears highlighted the more serious moments with the minutest of camera movements. Another outstanding two-hander, Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre (1981), is a valuable reference-point. Each episode included the week number (Week 1, Week 2 etc) in its title, so I watched them a week apart, not in twos, as they were transmitted, or by bingeing the whole 100 minutes on i-Player, as I’m sure many did, and I somehow think that was right. I imagine it will be back for another season and could well run and run.

Criminal (Netflix) has a larger cast but also a single set, in this case a police interrogation room, the adjoining surveillance room and the lift area/stairwell outside. It also has an interesting concept. There are four brief series, each made by a different country (UK, France, Spain and Germany) and each series (of 3) has a group of actors playing the police team across the three episodes and guest stars (like David Tennant)  playing the “criminals” being interrogated in each episode. Each investigation is a separate story, but there is a story arc across the three episodes involving the police characters. Unfortunately, the lack of back-story context or characterisation in the criminal stories is a hindrance, so there is no great tension in the interrogation scenes, compared to Line of Duty (or even 24 Hours in Police Custody). I haven’t watched every national version, so one of them may have cracked the format, but on the evidence I have seen (the UK and German series), I doubt it.

playing the “criminals” being interrogated in each episode. Each investigation is a separate story, but there is a story arc across the three episodes involving the police characters. Unfortunately, the lack of back-story context or characterisation in the criminal stories is a hindrance, so there is no great tension in the interrogation scenes, compared to Line of Duty (or even 24 Hours in Police Custody). I haven’t watched every national version, so one of them may have cracked the format, but on the evidence I have seen (the UK and German series), I doubt it.

Far better are two more traditional dramas, both also dealing with crime and police procedures, which most certainly rely on scenes of interview and interrogation rather than action. Season two of David Fincher’s Mindhunter (Netflix) built well on the excellent first series and continued to rely for its effectiveness mainly on the tense “interview” scenes in which imprisoned serial killers (based on real-life murderers and including, this season, Charles Manson) are questioned by the specialist FBI officers, trying to find psychological insights to help solve ongoing crimes (also based on real  examples – most prominently in this season, the Atlanta child murders). What is discussed is grisly in the extreme and comes across far more shockingly for being dispassionately spoken about than it would do if recreated for the drama. The private lives of Bill Tench (Holt McCallany) and Wendy Carr (Anna Torv) impact strongly on the narrative and the way the characters’ private experiences are shown to inform their innovative behavioural research (and vice versa) reminded me of a previous series: Masters of Sex (Showtime, 2013-16).

examples – most prominently in this season, the Atlanta child murders). What is discussed is grisly in the extreme and comes across far more shockingly for being dispassionately spoken about than it would do if recreated for the drama. The private lives of Bill Tench (Holt McCallany) and Wendy Carr (Anna Torv) impact strongly on the narrative and the way the characters’ private experiences are shown to inform their innovative behavioural research (and vice versa) reminded me of a previous series: Masters of Sex (Showtime, 2013-16).

ITV’s A Confession similarly located all its dramatic impetus in its dialogue, which was appropriate given that it was about what was and was not admissible as evidence and how following police procedures to the letter would not have achieved results. In this regard it was very similar to another ITV real-life police drama from earlier in the year: Manhunt. In the earlier piece, it was Martin Clunes playing the career copper who risked his position to follow his instinct. This time it is Martin Freeman, playing pretty much the same role – the Martins could have been interchangeable! It was an engaging, understated drama which kept the attention without setting the world on fire.

All of which, I guess, goes to show that you don’t necessarily need action sequences to produce an engaging drama, but the greatest pieces are likely to be those which find a balance between “action” and dialogue sequences, as long as the action is organic to the narrative and the dialogue is naturalistic rather than expository. Step forward, Top Boy  (Netflix). Having provided Channel 4 with two outstanding 4-part series in 2011 and 2013, Ronan Bennett’s Top Boy was then inexplicably dropped. But now, thanks to interest (and finance) from the rapper Drake, it is back on Netflix with a new 10-part season and the promise of more to come – and this is very good news. And the fact that the series has been so greatly expanded allows for many more back stories and for reflection on the circumstances the characters find themselves in – all of it highly pertinent to the recent rise in street crime and the headlines it has made.

(Netflix). Having provided Channel 4 with two outstanding 4-part series in 2011 and 2013, Ronan Bennett’s Top Boy was then inexplicably dropped. But now, thanks to interest (and finance) from the rapper Drake, it is back on Netflix with a new 10-part season and the promise of more to come – and this is very good news. And the fact that the series has been so greatly expanded allows for many more back stories and for reflection on the circumstances the characters find themselves in – all of it highly pertinent to the recent rise in street crime and the headlines it has made.

It also provides a large number of roles for an astonishing roster of young black British acting talent – some of the most impressive being the very youngest ones: Keiyon Cook and Araloyin Oshunremi outstanding as Ats and Stefan. Ashley Walters’ Dushane remains the main focus, though Kane Robinson as Sully and Micheal Ward as Jamie  complete a trio of riveting protagonists. Writing and direction are top-notch throughout, as is the music – both the original score by Brian Eno and the rap music which provides both impetus and comment. A key theme is the tension between the main characters’ involvement in drug wars and their attempts to engage in “normal” personal lives and look after family members, as well as the inevitable impact of the gang scene on the youngest members of the community. In this respect, it echoes The Godfather films in its epic scope.

complete a trio of riveting protagonists. Writing and direction are top-notch throughout, as is the music – both the original score by Brian Eno and the rap music which provides both impetus and comment. A key theme is the tension between the main characters’ involvement in drug wars and their attempts to engage in “normal” personal lives and look after family members, as well as the inevitable impact of the gang scene on the youngest members of the community. In this respect, it echoes The Godfather films in its epic scope.

We certainly need to be grateful to Drake for bringing about such a vital revival. I just wish that something similar would happen to another wonderful series abandoned by Channel 4 after two seasons and one of my very favourites of the past decade: Utopia.

Top Boy is a definite for my shortlist, and I will add Mindhunter to the list as well.

unfussy visuals; characters whose opinions and motivations evolve gradually; subtle yet powerful acting performances (Anna Maxwell-Martin, Daniel Mays, Vicky McClure). It ensured that all voices from the era of the Troubles were heard and understood, much as the Vanessa Engle documentary I highlighted from earlier in the year, The Funeral Murders, did. Indeed, the two pieces form a valuable diptych and, though they address issues from 25 and 30 years ago, have a similar contemporary resonance in reinforcing why the Irish border is the most important aspect of the Brexit process. Mother’s Day becomes the 9thprogramme on my running shortlist for the best of 2018.

unfussy visuals; characters whose opinions and motivations evolve gradually; subtle yet powerful acting performances (Anna Maxwell-Martin, Daniel Mays, Vicky McClure). It ensured that all voices from the era of the Troubles were heard and understood, much as the Vanessa Engle documentary I highlighted from earlier in the year, The Funeral Murders, did. Indeed, the two pieces form a valuable diptych and, though they address issues from 25 and 30 years ago, have a similar contemporary resonance in reinforcing why the Irish border is the most important aspect of the Brexit process. Mother’s Day becomes the 9thprogramme on my running shortlist for the best of 2018. to any that do at that point. First to arrive, and now nearing completion, was Jed Mercurio’s Bodyguard (BBC1, Sundays), an accomplished thriller (as one would expect from that source) which has been a big success and even had the confidence to kill off one of its lead characters halfway through and thus wrong-foot the audience, as it seemed to have been developing a compelling conflict-of-loyalty theme which is now redundant. It is manipulative and at times stretches credibility, but I’m hooked on it.

to any that do at that point. First to arrive, and now nearing completion, was Jed Mercurio’s Bodyguard (BBC1, Sundays), an accomplished thriller (as one would expect from that source) which has been a big success and even had the confidence to kill off one of its lead characters halfway through and thus wrong-foot the audience, as it seemed to have been developing a compelling conflict-of-loyalty theme which is now redundant. It is manipulative and at times stretches credibility, but I’m hooked on it. performances and the direction. The expansion of the narrative into the relationships of other characters (the couple’s friends, colleagues and children; Joy’s clients in her work as a therapist) is also highly engaging, but I did start to worry that it is beginning to stray into Cold Feet territory, potentially replicating the longevity and eventual repetitiveness of that series, so I’m not sure of the need to stay with it, but I probably will because: a) it’s as easy to watch as Cold Feet; and b) I’m still watching Cold Feet!

performances and the direction. The expansion of the narrative into the relationships of other characters (the couple’s friends, colleagues and children; Joy’s clients in her work as a therapist) is also highly engaging, but I did start to worry that it is beginning to stray into Cold Feet territory, potentially replicating the longevity and eventual repetitiveness of that series, so I’m not sure of the need to stay with it, but I probably will because: a) it’s as easy to watch as Cold Feet; and b) I’m still watching Cold Feet! since it was announced some three years ago) arrived on BBC2 last Monday. Black Earth Rising is the latest piece from my favourite television auteur, Hugo Blick (actually there aren’t many writer/director/producers around – Poliakoff is another, but they are few on the ground). If it turns out to be anywhere near as good as The Shadow Line (2011) or The Honourable Woman (2014), and early indications are that it will, then it will be an automatic choice for my top 10, but I will return to it later. So far it has contained Blick’s trademark expository scene-setting and has certain similarities to The Honourable Woman, but neither of these are particular drawbacks for me – it’s just great to be back in his intelligent and stylish world.

since it was announced some three years ago) arrived on BBC2 last Monday. Black Earth Rising is the latest piece from my favourite television auteur, Hugo Blick (actually there aren’t many writer/director/producers around – Poliakoff is another, but they are few on the ground). If it turns out to be anywhere near as good as The Shadow Line (2011) or The Honourable Woman (2014), and early indications are that it will, then it will be an automatic choice for my top 10, but I will return to it later. So far it has contained Blick’s trademark expository scene-setting and has certain similarities to The Honourable Woman, but neither of these are particular drawbacks for me – it’s just great to be back in his intelligent and stylish world.

comedy, so Saturdays are for sport, especially during the football season. It is not a night for drama, apart from the one exception to that rule, which I will come to below. Anyway, now that the first episode has aired, the whole thing is available on BBC i-player, which is how I will watch it in any spare moments between all the other fine series listed above.

comedy, so Saturdays are for sport, especially during the football season. It is not a night for drama, apart from the one exception to that rule, which I will come to below. Anyway, now that the first episode has aired, the whole thing is available on BBC i-player, which is how I will watch it in any spare moments between all the other fine series listed above. Sunday evening. Moving it away from its traditional Saturday home has been tried before and it failed miserably, though maybe in the era of catch-up services it will not matter so much. I worry that the bold experiment of a female Doctor, already tied to the success or otherwise of a new and potentially uncertain show-runner, will be fatally compromised by this blunder – or maybe it is a way of giving the traditionalists something else to focus on, rather than the gender of the lead actor, thus diverting attention from the biggest change and providing something easily rectified. We shall see.

Sunday evening. Moving it away from its traditional Saturday home has been tried before and it failed miserably, though maybe in the era of catch-up services it will not matter so much. I worry that the bold experiment of a female Doctor, already tied to the success or otherwise of a new and potentially uncertain show-runner, will be fatally compromised by this blunder – or maybe it is a way of giving the traditionalists something else to focus on, rather than the gender of the lead actor, thus diverting attention from the biggest change and providing something easily rectified. We shall see.

Engle’s The Funeral Murders (BBC2) aired back in March and was a harrowing description of two awful days in the history of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, told frankly, compassionately and impartially and with the benefit of 30 years of hindsight. Above all, it highlighted why the Irish border issue is not just one of the difficulties of the Brexit process but by far the most important issue. And last Friday, there was a splendid doc on the life and career of Olympic ice skater John Curry, The Ice King (BBC4), full of archival material and rare recordings of his work, though the fact that all the interviews seemed to be archival as well made it look a bit limited. The Funeral Murders is the one to make the shortlist.

Engle’s The Funeral Murders (BBC2) aired back in March and was a harrowing description of two awful days in the history of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, told frankly, compassionately and impartially and with the benefit of 30 years of hindsight. Above all, it highlighted why the Irish border issue is not just one of the difficulties of the Brexit process but by far the most important issue. And last Friday, there was a splendid doc on the life and career of Olympic ice skater John Curry, The Ice King (BBC4), full of archival material and rare recordings of his work, though the fact that all the interviews seemed to be archival as well made it look a bit limited. The Funeral Murders is the one to make the shortlist. story well told – but ultimately maybe just a bit too conventional to be regarded as something special. On the other hand, Russell T.Davies’ A Very English Scandal (BBC1), a three-part dramatization of the Jeremy Thorpe scandal of the seventies, was very special indeed. Davies’ triumph was to make a light, comedic piece out of an episode which, while full of laughable incompetence and colourful characters, also contained some pretty dark elements, and he did it without trivialising those aspects in any way. One line summed up that approach for me – a Liberal Party bigwig regretting that the Thorpe scandal had hit the party just when it was beginning to gain some momentum through the likes of Cyril Smith and Clement Freud. Wicked stuff! And Hugh Grant, while playing the comedy as we knew he could, was a revelation in portraying the deeper complexities of Thorpe. The fact that the case hit the headlines again at the time of transmission, through the news

story well told – but ultimately maybe just a bit too conventional to be regarded as something special. On the other hand, Russell T.Davies’ A Very English Scandal (BBC1), a three-part dramatization of the Jeremy Thorpe scandal of the seventies, was very special indeed. Davies’ triumph was to make a light, comedic piece out of an episode which, while full of laughable incompetence and colourful characters, also contained some pretty dark elements, and he did it without trivialising those aspects in any way. One line summed up that approach for me – a Liberal Party bigwig regretting that the Thorpe scandal had hit the party just when it was beginning to gain some momentum through the likes of Cyril Smith and Clement Freud. Wicked stuff! And Hugh Grant, while playing the comedy as we knew he could, was a revelation in portraying the deeper complexities of Thorpe. The fact that the case hit the headlines again at the time of transmission, through the news  that the incompetent assassin Andrew Newton is still alive, when the police thought he was dead, only added to the sense of event television, as did the screening of Tom Bower’s edition of Panorama, scheduled for the night in 1979 when the expected guilty verdict should have been delivered, but shelved when it wasn’t. The inclusion of Peter Cook’s contemporary satire of the judge’s biased summing up during the end credits was a master stroke, too. A Very English Scandal is very much one for the shortlist.

that the incompetent assassin Andrew Newton is still alive, when the police thought he was dead, only added to the sense of event television, as did the screening of Tom Bower’s edition of Panorama, scheduled for the night in 1979 when the expected guilty verdict should have been delivered, but shelved when it wasn’t. The inclusion of Peter Cook’s contemporary satire of the judge’s biased summing up during the end credits was a master stroke, too. A Very English Scandal is very much one for the shortlist. Melrose’s self-destructive character was the fault of his abusive father and negligent mother, there was nothing else to it. It rather reminded me of a previous lavish five-parter, also featuring a fine performance from Benedict Cumberbatch and also based on a series of highly-regarded novels, Parade’s End (BBC, 2012), which ultimately did not add up to the sum of its parts.

Melrose’s self-destructive character was the fault of his abusive father and negligent mother, there was nothing else to it. It rather reminded me of a previous lavish five-parter, also featuring a fine performance from Benedict Cumberbatch and also based on a series of highly-regarded novels, Parade’s End (BBC, 2012), which ultimately did not add up to the sum of its parts.

especially this version of it, so the fact that it was available on a set which was (and still is) on sale for under a tenner was an opportunity not to be missed. I would gladly have paid double for the silent version alone.

especially this version of it, so the fact that it was available on a set which was (and still is) on sale for under a tenner was an opportunity not to be missed. I would gladly have paid double for the silent version alone. have bought the silent German bergfilm The Holy Mountain had the set not come with a bonus disc containing the excellent three-hour documentary The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl (Ray Muller, 1993). It is there because Riefenstahl stars in The Holy Mountain, but otherwise has nothing to do with that film beyond the brief section on her acting career.

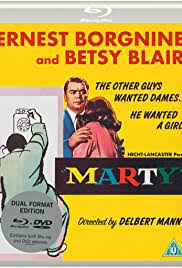

have bought the silent German bergfilm The Holy Mountain had the set not come with a bonus disc containing the excellent three-hour documentary The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl (Ray Muller, 1993). It is there because Riefenstahl stars in The Holy Mountain, but otherwise has nothing to do with that film beyond the brief section on her acting career. of Marty amongst this Eureka release’s special features which was the top selling point for me. It was transmitted as part of NBC’s Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse, a strand which was the recipient of a 1953 Peabody Award for the general excellence of its productions, so it wasn’t only the film version which won prestigious awards. It had previously been available only on a US-standard Criterion set called The Golden Age of Television and some interviews from that set are included as well.

of Marty amongst this Eureka release’s special features which was the top selling point for me. It was transmitted as part of NBC’s Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse, a strand which was the recipient of a 1953 Peabody Award for the general excellence of its productions, so it wasn’t only the film version which won prestigious awards. It had previously been available only on a US-standard Criterion set called The Golden Age of Television and some interviews from that set are included as well.

Now don’t get me wrong. I have happily followed many series primarily because of engagement with the characters. I never missed an episode of Hill Street Blues or NYPD Blue. These, though, could be relied upon to provide constantly engaging and occasionally startling narratives and, as dramas with contemporary settings, had scope for re-invention. And, although they had their high points, those series never failed to deliver, even when past their best – unlike, say, Homeland, another series I have watched throughout, despite several very rocky seasons until its more recent revival (I thought the last season, dealing with the Presidential transition, was the best since the brilliant first season – maybe even better than it).

Now don’t get me wrong. I have happily followed many series primarily because of engagement with the characters. I never missed an episode of Hill Street Blues or NYPD Blue. These, though, could be relied upon to provide constantly engaging and occasionally startling narratives and, as dramas with contemporary settings, had scope for re-invention. And, although they had their high points, those series never failed to deliver, even when past their best – unlike, say, Homeland, another series I have watched throughout, despite several very rocky seasons until its more recent revival (I thought the last season, dealing with the Presidential transition, was the best since the brilliant first season – maybe even better than it). series as George R.R.Martin has written them. Much the same is happening on a smaller scale with Wolf Hall (and we already KNOW how that will end!). Most interestingly, The Leftovers adapted Tom Perrotta’s complete novel in its first season, with the novelist as co-screenwriter, and continued and completed the story this way in seasons 2 and 3, but without any further novels appearing.

series as George R.R.Martin has written them. Much the same is happening on a smaller scale with Wolf Hall (and we already KNOW how that will end!). Most interestingly, The Leftovers adapted Tom Perrotta’s complete novel in its first season, with the novelist as co-screenwriter, and continued and completed the story this way in seasons 2 and 3, but without any further novels appearing. Exhibit A is Broadchurch, which I would remember as one of ITV’s great recent dramas if it had ended where it should have, after what became the first season. But a series which is both a major commercial and critical success is something TV cannot resist trying to replicate, and I was so disappointed by the way the second season stretched credibility in order to perpetuate itself, that I gave up on it. I made it all the way through the second season of The Fall (BBC2), which I thought was excellent until the final seconds of the final episode but the lack of a conclusive ending and the subsequent attempt to stretch it further so alienated me that I resolved to avoid the third season. Did anybody watch it? Was it any good? There have been some successes, though: Happy Valley came back just as strong for its second season and Peaky Blinders found the missing ingredient that Boardwalk Empire lacked.

Exhibit A is Broadchurch, which I would remember as one of ITV’s great recent dramas if it had ended where it should have, after what became the first season. But a series which is both a major commercial and critical success is something TV cannot resist trying to replicate, and I was so disappointed by the way the second season stretched credibility in order to perpetuate itself, that I gave up on it. I made it all the way through the second season of The Fall (BBC2), which I thought was excellent until the final seconds of the final episode but the lack of a conclusive ending and the subsequent attempt to stretch it further so alienated me that I resolved to avoid the third season. Did anybody watch it? Was it any good? There have been some successes, though: Happy Valley came back just as strong for its second season and Peaky Blinders found the missing ingredient that Boardwalk Empire lacked.