This evening in New York the 30 winners of the 2017 Peabody Awards, together with two institutions and one individual, will receive their small but highly prestigious trophies at a ceremony on Wall Street. There are no categories, no envelopes and no nominees. We already know who the winners are. The list is here: http://www.peabodyawards.com/stories/story/2017-peabody-award-winners-77th-annual-peabody-30

I was fortunate and privileged to serve on the Peabody Board of Jurors from 2011 to 2016 and know well how many hours, days, weeks and months of viewing, discussing and deliberating goes into reducing over 1,200 submissions to the final thirty. It is an exhausting and exhilarating process which always produces a list of titles worth exploring. If, like me, you endured another year of frustrating and mystifying decisions at this year’s Baftas last Sunday, I can recommend you check out the Peabody list. The vast majority of the submissions are American, and this year’s list of winners is even more dominated by US product than in most previous years, but the process of deliberation is so trustworthy that what wins is not really a matter for contention. Unlike the Baftas, where you know what has been chosen over what else in each category and can get upset about it, the Peabody list is simply a collection of great stuff and there is  little point in criticising inclusions or fretting over exclusions – 16 highly-qualified and carefully chosen judges have already done that for us and have agreed unanimously on the outcome.

little point in criticising inclusions or fretting over exclusions – 16 highly-qualified and carefully chosen judges have already done that for us and have agreed unanimously on the outcome.

That said, not everything on the list will be to everybody’s taste. When I was on the Board, I was able and obliged to watch everything which received serious consideration. For the last two years, since I left the Board, I have used the list as a totally reliable guide to select what to watch in a crowded market – last year I was particularly knocked out by Louis CK’s Horace and Pete. Not everything on the list is going to be available outside the USA – the fact that material on the PBS website won’t play outside the States is as frustrating as the unavailability of stuff on the BBC i-Player must be to people outside Britain (and it’s done for the same reason). But many of the entertainment and documentary titles can be found on various platforms such as Netflix and Amazon (even some of the PBS stuff) and I have enjoyed watching a number of the things I had not already seen in the past few weeks since the list was announced.

First to be published were the documentary winners and I watched Chasing Coral and Newtown on Netflix, which carries the latter despite it being a PBS title from the outstanding Independent Lens series. Newtown is a very moving study of the effects of the Sandy Hook school massacre on the Connecticut community. The documentary I would most like to see, though, is Deej, which I cannot find available anywhere in Britain as yet – hopefully it will come our way some time soon.

From the entertainment list, published a week later, I checked out Hasan Minhaj: Homecoming King on Netflix – a stand-up comedy special which is not only very funny, but truly thought-provoking and well-designed for television presentation. Minhaj is hosting tonight’s ceremony, so it will be fun to see how that works. I also looked at The Marvellous Mrs Maisel on Amazon, but I’m afraid I didn’t get further than the first episode – as I said, not everything appeals to everybody.

But there are two things from this year’s list of Peabody winners which have more than re-confirmed my faith in it as the best guide to quality viewing and which I may not otherwise have discovered – one from the documentary list, the other from entertainment, and both available on Netflix. Time: the Kalief Browder Story (Weinstein Television – and, yes, Harvey’s name is even on the credits!) is a documentary series about injustice in the tradition of Making a Murderer. It tells the horrific tale of a  young black man whose refusal to plea bargain over an alleged minor felony kept him in the “justice system” for three years, involving incarceration in New York’s notorious Rikers Island prison and several lengthy spells in solitary confinement, before his eventual release and exoneration preceded a tragic ending. With extensive forensic interviews and disturbing CCTV footage, the series grips and shocks over six episodes, but it is the nature of the injustices and abuses it uncovers rather than the style of storytelling which makes the greatest impact – and that is just as well, because the other series I am going to describe is such a perfect parody of the genre that it’s going to make it difficult to watch such things in future without thinking about it.

young black man whose refusal to plea bargain over an alleged minor felony kept him in the “justice system” for three years, involving incarceration in New York’s notorious Rikers Island prison and several lengthy spells in solitary confinement, before his eventual release and exoneration preceded a tragic ending. With extensive forensic interviews and disturbing CCTV footage, the series grips and shocks over six episodes, but it is the nature of the injustices and abuses it uncovers rather than the style of storytelling which makes the greatest impact – and that is just as well, because the other series I am going to describe is such a perfect parody of the genre that it’s going to make it difficult to watch such things in future without thinking about it.

I’m certainly glad I watched The Kalief Browder Story before I came across American Vandal (3 Arts/Funny or Die). Taking its cue from series like The Jinx, Making a Murderer and Serial, it is a hilarious genre parody in which two high-school media nerds investigate who was responsible for spray-painting 27 penises on cars in the school staff car park, in an attempt to prove the innocence of the suspended prime suspect. The humour is pitch-perfect, but the joke could not have been stretched across eight episodes if it had not been much more besides. The characters are so well drawn that it works as comedy-drama as well – imagine My So-Called Life re-made in the style of The Office. It also has plenty to say about the nature of documentary truth and the effect of such programming on people’s lives in the age of social media.

Unfortunately, these being programmes from 2017, neither can go on my running list of the best of 2018, even though I’ve only just caught up with them. But the latest season of a Peabody winner from 2011 certainly can. I first encountered Homeland (Showtime) as part of my Peabody viewing and it was on the winners’ list in its first season. Despite the fact that it then suffered something of a slump, I have followed it ever since and am delighted that it has been reviving over the past three years: so much so that I think the latest season, just finished on Channel 4, is the best since the first – maybe it’s even better. No other dramatic series manages to keep its finger on the pulse of contemporary events as strikingly as Homeland has done over the past two seasons, which is even more amazing when you consider the lead-in times involved. The current threats to American democracy – Russia, media manipulation, Presidential hubris – are all in there and Carrie’s bi-polar disorder is a perfect metaphor for the divisive nature of current American politics and society.

Homeland is thus the first American title on my 2018 shortlist, though the best stuff from the States has usually arrived here in the Summer in recent years (see my first blog!), so I’m certain it won’t be the last. And I still have a good deal of catching up to do on Netflix and Amazon (I’m currently enjoying The Looming Tower on the latter). Maybe I’ll have managed to see more of the 2018 Peabody winners, at least in the entertainment section, before the list is published next year. I’ll certainly be awaiting it as eagerly as ever.

especially this version of it, so the fact that it was available on a set which was (and still is) on sale for under a tenner was an opportunity not to be missed. I would gladly have paid double for the silent version alone.

especially this version of it, so the fact that it was available on a set which was (and still is) on sale for under a tenner was an opportunity not to be missed. I would gladly have paid double for the silent version alone. have bought the silent German bergfilm The Holy Mountain had the set not come with a bonus disc containing the excellent three-hour documentary The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl (Ray Muller, 1993). It is there because Riefenstahl stars in The Holy Mountain, but otherwise has nothing to do with that film beyond the brief section on her acting career.

have bought the silent German bergfilm The Holy Mountain had the set not come with a bonus disc containing the excellent three-hour documentary The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl (Ray Muller, 1993). It is there because Riefenstahl stars in The Holy Mountain, but otherwise has nothing to do with that film beyond the brief section on her acting career. of Marty amongst this Eureka release’s special features which was the top selling point for me. It was transmitted as part of NBC’s Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse, a strand which was the recipient of a 1953 Peabody Award for the general excellence of its productions, so it wasn’t only the film version which won prestigious awards. It had previously been available only on a US-standard Criterion set called The Golden Age of Television and some interviews from that set are included as well.

of Marty amongst this Eureka release’s special features which was the top selling point for me. It was transmitted as part of NBC’s Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse, a strand which was the recipient of a 1953 Peabody Award for the general excellence of its productions, so it wasn’t only the film version which won prestigious awards. It had previously been available only on a US-standard Criterion set called The Golden Age of Television and some interviews from that set are included as well.

attempt to merge Scandi-noir with the vogue for crime mysteries in enclosed communities.

attempt to merge Scandi-noir with the vogue for crime mysteries in enclosed communities.

one great and a great one outstanding – and this is a great script. A great cast, too, also including fine work from Suranne Jones and Kerry Godliman, alongside Graham and the others, and a brief yet indelible cameo from Adrian Edmondson.

one great and a great one outstanding – and this is a great script. A great cast, too, also including fine work from Suranne Jones and Kerry Godliman, alongside Graham and the others, and a brief yet indelible cameo from Adrian Edmondson.

Walter’s friend Bagpipes and Kellie Shirley as his wife Kirsty. This is an excellent role for Bailey – a wonderful stand-up but hitherto underused as a comic actor. Bailey and Elba are particularly good in their scenes together. The racial politics of the time are a constant presence and reference point, without becoming overwhelming.

Walter’s friend Bagpipes and Kellie Shirley as his wife Kirsty. This is an excellent role for Bailey – a wonderful stand-up but hitherto underused as a comic actor. Bailey and Elba are particularly good in their scenes together. The racial politics of the time are a constant presence and reference point, without becoming overwhelming.

unbearably difficult to leave his mum, both because of the loss of his father and his own domestic needs – meals and washing – which Kelly seems very unlikely to provide for him; Derek and Pauline waiting for the latter’s divorce to be finalised and hiding their own desperate insecurities behind their rather pathetic public personas; and Maureen and Reg, usually in the background, Maureen asleep and Reg seemingly waiting for the moment he will lose his wife as well, all the time tenderly checking that she is still alive, in between swearing and complaining about everything else.

unbearably difficult to leave his mum, both because of the loss of his father and his own domestic needs – meals and washing – which Kelly seems very unlikely to provide for him; Derek and Pauline waiting for the latter’s divorce to be finalised and hiding their own desperate insecurities behind their rather pathetic public personas; and Maureen and Reg, usually in the background, Maureen asleep and Reg seemingly waiting for the moment he will lose his wife as well, all the time tenderly checking that she is still alive, in between swearing and complaining about everything else. or doesn’t happen, we are going to miss it when it’s gone. It really seems superfluous to note that the acting performances are out-of-this-world wonderful, but, equally, it would be an oversight to write a blog about Mum without mentioning just how fantastic Lesley Manville and Peter Mullan are, as are all the cast (and a special mention for Karl Johnson as Reg this time round). So much goes unspoken, but you are in no doubt what the characters are thinking and feeling. One other point about the third series – it will be interesting to see how the episodes are titled. So far, each episode has had the name of a month as its title (each season covering a year in the characters’ lives), but all 12 have been used up now.

or doesn’t happen, we are going to miss it when it’s gone. It really seems superfluous to note that the acting performances are out-of-this-world wonderful, but, equally, it would be an oversight to write a blog about Mum without mentioning just how fantastic Lesley Manville and Peter Mullan are, as are all the cast (and a special mention for Karl Johnson as Reg this time round). So much goes unspoken, but you are in no doubt what the characters are thinking and feeling. One other point about the third series – it will be interesting to see how the episodes are titled. So far, each episode has had the name of a month as its title (each season covering a year in the characters’ lives), but all 12 have been used up now.

watching John Cleese, Alison Steadman and Jason Watkins effortlessly investing substandard dialogue with the sort of comic potential it doesn’t deserve. The rest of the high-quality cast, including the aforementioned Joanna Scanlan and sitcom veteran Peter Egan, were largely wasted, though. And, unlike the other two shows, it was really trying to be funny.

watching John Cleese, Alison Steadman and Jason Watkins effortlessly investing substandard dialogue with the sort of comic potential it doesn’t deserve. The rest of the high-quality cast, including the aforementioned Joanna Scanlan and sitcom veteran Peter Egan, were largely wasted, though. And, unlike the other two shows, it was really trying to be funny.

subtitled A Personal View by Kenneth Clark. Clark himself had become a well-known presenter of documentaries on art, especially painting, throughout the fifties and sixties, but this was the first time (of many more to come) that an expert presenter had fronted a prestige 13-part series and, though the aim was a comprehensive overview of his subject, that subject needed to be clearly defined (and clearly wasn’t).

subtitled A Personal View by Kenneth Clark. Clark himself had become a well-known presenter of documentaries on art, especially painting, throughout the fifties and sixties, but this was the first time (of many more to come) that an expert presenter had fronted a prestige 13-part series and, though the aim was a comprehensive overview of his subject, that subject needed to be clearly defined (and clearly wasn’t). being that he may not be able to define it positively, but he can certainly recognise the opposite – and, where Clark begins his narrative with the Dark Ages and the survival of civilisation during an age of barbarian vandalism “by the skin of our teeth”, so Schama invokes the cultural destructiveness of ISIS to illustrate the fragility of civilisation (and at the same time tells the story of Khaled al-Asaad, the ultimate archivist, who preferred execution to revealing the whereabouts of Palmyra’s treasures). Then on to the opening titles – in which the title “Civilisation” first appears, with the final S formed as an addition from matter floating about the screen. The connection to the original series is unambiguously made.

being that he may not be able to define it positively, but he can certainly recognise the opposite – and, where Clark begins his narrative with the Dark Ages and the survival of civilisation during an age of barbarian vandalism “by the skin of our teeth”, so Schama invokes the cultural destructiveness of ISIS to illustrate the fragility of civilisation (and at the same time tells the story of Khaled al-Asaad, the ultimate archivist, who preferred execution to revealing the whereabouts of Palmyra’s treasures). Then on to the opening titles – in which the title “Civilisation” first appears, with the final S formed as an addition from matter floating about the screen. The connection to the original series is unambiguously made. well as venturing well beyond Western Europe, establishes the difference in time as well as space. The second part brings even more points of comparison and difference – most obviously, there is a different presenter, Mary Beard, who will contribute two parts to the series, as will David Olusoga, while Schama returns for a further four. This has the desired effect of introducing more diverse voices and each part is clearly labelled as the personal view of the presenter. Whether this fragmentation helps the coherence of the series is another matter, as is the related decision to divide the narrative thematically rather than chronologically. Beard’s first foray contains more direct correctives to the original than seen so far, including a clip of Clark delivering the sort of “elitist” judgements here being disclaimed. Beard has clearly been included amongst the presenters to provide a much-needed feminist perspective, but she rather overstepped the brief in the widely derided sequence in which she told a story of a man who ejaculated on an ancient statue of Aphrodite and claimed this was rape because the statue had not consented! To me, the problem here was not so much the plain silliness of the assertion, inserted in a spirit of political correctness to make a connection with a current issue, but the lost opportunity it represented to explore ideas about the fine line between art and pornography. To be fair to Beard, she recovered from this low point to give us one of the better episodes – the one on religion and art (part 4: The Eye of Faith) – which she ended with her own take on the meaning of “civilisation” as an “act of faith”.

well as venturing well beyond Western Europe, establishes the difference in time as well as space. The second part brings even more points of comparison and difference – most obviously, there is a different presenter, Mary Beard, who will contribute two parts to the series, as will David Olusoga, while Schama returns for a further four. This has the desired effect of introducing more diverse voices and each part is clearly labelled as the personal view of the presenter. Whether this fragmentation helps the coherence of the series is another matter, as is the related decision to divide the narrative thematically rather than chronologically. Beard’s first foray contains more direct correctives to the original than seen so far, including a clip of Clark delivering the sort of “elitist” judgements here being disclaimed. Beard has clearly been included amongst the presenters to provide a much-needed feminist perspective, but she rather overstepped the brief in the widely derided sequence in which she told a story of a man who ejaculated on an ancient statue of Aphrodite and claimed this was rape because the statue had not consented! To me, the problem here was not so much the plain silliness of the assertion, inserted in a spirit of political correctness to make a connection with a current issue, but the lost opportunity it represented to explore ideas about the fine line between art and pornography. To be fair to Beard, she recovered from this low point to give us one of the better episodes – the one on religion and art (part 4: The Eye of Faith) – which she ended with her own take on the meaning of “civilisation” as an “act of faith”. audience this is aimed at. Those old enough to remember the original will (hopefully) have gone through a long process, aided by countless TV arts and history series, of gaining a greater perspective on world cultural history. Those who don’t remember it, or don’t even know about it, will understand that attitudes have changed and may wonder why the point is being emphasised at all.

audience this is aimed at. Those old enough to remember the original will (hopefully) have gone through a long process, aided by countless TV arts and history series, of gaining a greater perspective on world cultural history. Those who don’t remember it, or don’t even know about it, will understand that attitudes have changed and may wonder why the point is being emphasised at all.

children’s schedules (and my own viewing) when I first started watching TV in the late 1950s. ITV had just begun and imported a large number of American titles, with the BBC following suit to compete. My particular favourites were The Lone Ranger (ABC, 1949-57), Wagon Train (NBC, 1957-62), Maverick (ABC, 1957-62), Bonanza (NBC, 1959-73) and, above all, Rawhide (CBS, 1959-65). However, the genre all but disappeared from TV (and, indeed, the cinema) from the late sixties onwards. There were many reasons for this – socio-political, cultural and economic – though there were the occasional revivals in both cinema (mostly thanks to former TV cowboy Clint Eastwood) and TV (1989’s Lonesome Dove), but then nothing of real impact until….

children’s schedules (and my own viewing) when I first started watching TV in the late 1950s. ITV had just begun and imported a large number of American titles, with the BBC following suit to compete. My particular favourites were The Lone Ranger (ABC, 1949-57), Wagon Train (NBC, 1957-62), Maverick (ABC, 1957-62), Bonanza (NBC, 1959-73) and, above all, Rawhide (CBS, 1959-65). However, the genre all but disappeared from TV (and, indeed, the cinema) from the late sixties onwards. There were many reasons for this – socio-political, cultural and economic – though there were the occasional revivals in both cinema (mostly thanks to former TV cowboy Clint Eastwood) and TV (1989’s Lonesome Dove), but then nothing of real impact until…. for so much of the f-ing and c-ing in the dialogue, but one which belonged to the real-life individual on whom the character is based. Indeed, most of the characters in Deadwood are based on the town’s original inhabitants and the narrative is closely tied to the historical reality and to examining the development of social, political and economic structures which emerged from the anarchy of the pioneering west; and within this narrative, Milch and his terrific cast create characters who have both a historic and contemporary resonance, which is why it works so well.

for so much of the f-ing and c-ing in the dialogue, but one which belonged to the real-life individual on whom the character is based. Indeed, most of the characters in Deadwood are based on the town’s original inhabitants and the narrative is closely tied to the historical reality and to examining the development of social, political and economic structures which emerged from the anarchy of the pioneering west; and within this narrative, Milch and his terrific cast create characters who have both a historic and contemporary resonance, which is why it works so well. activities of the mineral pioneers, through the importance of the press in the development of the west and its mythology to the depiction of lesbian relationships. However, having watched it immediately after finishing Deadwood, its differences are more striking: it has much more in the way of open spaces, whereas Deadwood is almost completely confined to the town, which gives it a claustrophobic feel (rather like that of NYPD Blue); it also has more in the way of traditional western tropes (the “cowardly” sheriff redeemed at the end; the mysterious stranger who acts as a mentor to a young boy, before riding off into the sunset; a climactic shootout worthy of Sam Peckinpah) despite the “twist” that it features a large number of female protagonists; basically it looks like an extended movie rather than a TV series (shot in a 2.39:1 ratio; complete at just over 7 hours, or less than twice the running time of Heaven’s Gate). It is also mightily impressive and enjoyable and a significant addition to the western canon on both film and TV.

activities of the mineral pioneers, through the importance of the press in the development of the west and its mythology to the depiction of lesbian relationships. However, having watched it immediately after finishing Deadwood, its differences are more striking: it has much more in the way of open spaces, whereas Deadwood is almost completely confined to the town, which gives it a claustrophobic feel (rather like that of NYPD Blue); it also has more in the way of traditional western tropes (the “cowardly” sheriff redeemed at the end; the mysterious stranger who acts as a mentor to a young boy, before riding off into the sunset; a climactic shootout worthy of Sam Peckinpah) despite the “twist” that it features a large number of female protagonists; basically it looks like an extended movie rather than a TV series (shot in a 2.39:1 ratio; complete at just over 7 hours, or less than twice the running time of Heaven’s Gate). It is also mightily impressive and enjoyable and a significant addition to the western canon on both film and TV.

is a masterclass in how to follow these rules. The first time Cynthia Nixon appears (replacing Emma Bell, who plays the young Dickinson), she is being introduced by her sister and is then asked about her schooldays (“but that was many years ago”). Job done – though, just to be clear, Davies has already shown us the one actress digitally morph into the other while posing for a photograph and he further emphasises the point in the closing credits by showing a portrait of Nixon as Dickinson which morphs back into one of Bell and then into the only known daguerreotype of Dickinson, showing the strong resemblance between Bell and the real Dickinson.

is a masterclass in how to follow these rules. The first time Cynthia Nixon appears (replacing Emma Bell, who plays the young Dickinson), she is being introduced by her sister and is then asked about her schooldays (“but that was many years ago”). Job done – though, just to be clear, Davies has already shown us the one actress digitally morph into the other while posing for a photograph and he further emphasises the point in the closing credits by showing a portrait of Nixon as Dickinson which morphs back into one of Bell and then into the only known daguerreotype of Dickinson, showing the strong resemblance between Bell and the real Dickinson.  portray a character’s ageing? I guess the answer is “whatever works”. The outstanding 1984 German series Heimat, which follows life in a Hunsruck village through the 20

portray a character’s ageing? I guess the answer is “whatever works”. The outstanding 1984 German series Heimat, which follows life in a Hunsruck village through the 20 Flannery’s Our Friends in the North (BBC, 1996), in which the lives of four friends were followed from the sixties to the nineties, with the same actors – breakthrough roles for Christopher Eccleston, Daniel Craig, Gina McKee and Mark Strong – employed throughout.

Flannery’s Our Friends in the North (BBC, 1996), in which the lives of four friends were followed from the sixties to the nineties, with the same actors – breakthrough roles for Christopher Eccleston, Daniel Craig, Gina McKee and Mark Strong – employed throughout.  reference, given that the very first Doctor Who was transmitted the day after the events in Dallas (the city, not the show). To take this ludicrous suggestion even further, we have known since the Doctor Who Christmas special (much earlier, really) that the Doctor can even change sex (or, to be more precise, that they can change the sex of the actor portraying him/her), so, if traditionally male roles can now be played by women, why not have a future incarnation of the Queen on The Crown played by a man? I think Eddie Izzard would be good.

reference, given that the very first Doctor Who was transmitted the day after the events in Dallas (the city, not the show). To take this ludicrous suggestion even further, we have known since the Doctor Who Christmas special (much earlier, really) that the Doctor can even change sex (or, to be more precise, that they can change the sex of the actor portraying him/her), so, if traditionally male roles can now be played by women, why not have a future incarnation of the Queen on The Crown played by a man? I think Eddie Izzard would be good.

includes It’s a Royal Knockout!), to William and Harry; problematic marriages and clandestine affairs from the ones currently being portrayed to the even more public scandals of Charles and Diana, Andrew and Fergie and who-knows-what to come; struggles for control of the “family business”, with the remaining older generation such as the Queen Mother and Lord Mountbatten always trying to interfere, not to mention the troublesome Windsors.

includes It’s a Royal Knockout!), to William and Harry; problematic marriages and clandestine affairs from the ones currently being portrayed to the even more public scandals of Charles and Diana, Andrew and Fergie and who-knows-what to come; struggles for control of the “family business”, with the remaining older generation such as the Queen Mother and Lord Mountbatten always trying to interfere, not to mention the troublesome Windsors.

define what a TV drama in 2017 could be as brilliantly as that original series did back in 1990. It was the unmissable highlight of the year over 18 hour-long segments, though David Lynch, who directed it all as compellingly as he has ever directed anything (episode 8 was particularly stunning), said he preferred to see it as an 18-hour film and it did, indeed, make several “best film” lists (see my previous blog).

define what a TV drama in 2017 could be as brilliantly as that original series did back in 1990. It was the unmissable highlight of the year over 18 hour-long segments, though David Lynch, who directed it all as compellingly as he has ever directed anything (episode 8 was particularly stunning), said he preferred to see it as an 18-hour film and it did, indeed, make several “best film” lists (see my previous blog). but not in the version transmitted on BBC4, which was about half that length. Having now seen the full version on DVD, I cannot imagine why we didn’t get the full PBS version. There is nothing superfluous about the material which didn’t make the cut, nor anything which would be of interest to a US audience only. It is all wonderful documentary making and, being twice as long, the full version is literally twice as good. It’s the best thing Burns has done since The Civil War (and he has given us some great things in the years between).

but not in the version transmitted on BBC4, which was about half that length. Having now seen the full version on DVD, I cannot imagine why we didn’t get the full PBS version. There is nothing superfluous about the material which didn’t make the cut, nor anything which would be of interest to a US audience only. It is all wonderful documentary making and, being twice as long, the full version is literally twice as good. It’s the best thing Burns has done since The Civil War (and he has given us some great things in the years between). are thus absolute musts for my top ten of the year. Firstly, Damon Lindelof and Tom Perrotta’s

are thus absolute musts for my top ten of the year. Firstly, Damon Lindelof and Tom Perrotta’s  Arts), created by Maya Ilsoe. Unlike previous Danish dramas, like The Killing or Borgen, this has been tucked away on a niche channel and, although press and online sources drew attention to the first two seasons, the third was virtually unheralded. The plotlines were occasionally a little melodramatic, but this was a series to be watched above all for the acting, which was both intense and subtle throughout, but utterly brilliant from the whole cast, especially Trine Dyrholm as Gro and Carsten Bjornlund as Frederick.

Arts), created by Maya Ilsoe. Unlike previous Danish dramas, like The Killing or Borgen, this has been tucked away on a niche channel and, although press and online sources drew attention to the first two seasons, the third was virtually unheralded. The plotlines were occasionally a little melodramatic, but this was a series to be watched above all for the acting, which was both intense and subtle throughout, but utterly brilliant from the whole cast, especially Trine Dyrholm as Gro and Carsten Bjornlund as Frederick. nobody does this sort of thing better than Jimmy McGovern and he was back with

nobody does this sort of thing better than Jimmy McGovern and he was back with  Rochdale sexual abuse scandal with sensitivity and incisiveness. Writer Nicole Taylor and director Philippa Lowthorpe (whose documentary background was a key element) produced a work of rare insight, but the main kudos go to the three young actresses who played the girls, alongside established stars like Maxine Peake and Lesley Sharp.

Rochdale sexual abuse scandal with sensitivity and incisiveness. Writer Nicole Taylor and director Philippa Lowthorpe (whose documentary background was a key element) produced a work of rare insight, but the main kudos go to the three young actresses who played the girls, alongside established stars like Maxine Peake and Lesley Sharp. output. Whereas he previously used a faux naivete to encourage his subjects to reveal themselves, he now befriends them and displays a genuine empathy towards them, which allows him to speak frankly. In his latest series,

output. Whereas he previously used a faux naivete to encourage his subjects to reveal themselves, he now befriends them and displays a genuine empathy towards them, which allows him to speak frankly. In his latest series,

had asked for. The truly great comedy revival of the year was last week’s three-part

had asked for. The truly great comedy revival of the year was last week’s three-part

poll, as though this somehow represents a fatal point of no return for the primacy of cinema to those who believe in such a thing. Maybe it does, though it is a very thin end of the wedge so far – I can think of several more TV series which are superior to many of the traditional films on the list. What is more, of all the TV series on offer, Twin Peaks best fits the profile of what a film critic would find acceptable – not only did David Lynch say that he saw it as a long film cut up into parts, but he directed it all himself (unlike the 1990-1 series). And never mind that the film which topped the poll was the “big screen” directorial debut of a TV comedy star (not mentioned in the lengthy and otherwise excellent essay in S&S) – far more subversive is the presence of the other TV drama series in the top 40, The Handmaid’s Tale, way down at the bottom. Titles on the list are all followed (traditionally) by the director’s name, but The Handmaid’s Tale is credited to Bruce Miller, who is the “show runner” and wrote many of the episodes, but didn’t direct any of it. This acknowledgement of the validity of a different way of doing things, if it is such, is a big step.

poll, as though this somehow represents a fatal point of no return for the primacy of cinema to those who believe in such a thing. Maybe it does, though it is a very thin end of the wedge so far – I can think of several more TV series which are superior to many of the traditional films on the list. What is more, of all the TV series on offer, Twin Peaks best fits the profile of what a film critic would find acceptable – not only did David Lynch say that he saw it as a long film cut up into parts, but he directed it all himself (unlike the 1990-1 series). And never mind that the film which topped the poll was the “big screen” directorial debut of a TV comedy star (not mentioned in the lengthy and otherwise excellent essay in S&S) – far more subversive is the presence of the other TV drama series in the top 40, The Handmaid’s Tale, way down at the bottom. Titles on the list are all followed (traditionally) by the director’s name, but The Handmaid’s Tale is credited to Bruce Miller, who is the “show runner” and wrote many of the episodes, but didn’t direct any of it. This acknowledgement of the validity of a different way of doing things, if it is such, is a big step. Alexander (the first part of which, incidentally, has to be the greatest Christmas movie of all). Indeed, the feature versions of the first two were simply cut down versions of the TV series. In Germany, Rainer Werner Fassbinder was prolific in television – not just the celebrated Berlin Alexanderplatz, but also the “family series” Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day (which I have only just caught up with, thanks to the Arrow release) and World on a Wire. I first saw Berlin Alexanderplatz at an exhausting but exhilarating all-weekend screening in NFT1, and Edgar Reitz’s Heimat, which for me is the greatest TV drama series of all, was also first available as an even more memorable two-day cinema marathon.

Alexander (the first part of which, incidentally, has to be the greatest Christmas movie of all). Indeed, the feature versions of the first two were simply cut down versions of the TV series. In Germany, Rainer Werner Fassbinder was prolific in television – not just the celebrated Berlin Alexanderplatz, but also the “family series” Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day (which I have only just caught up with, thanks to the Arrow release) and World on a Wire. I first saw Berlin Alexanderplatz at an exhausting but exhilarating all-weekend screening in NFT1, and Edgar Reitz’s Heimat, which for me is the greatest TV drama series of all, was also first available as an even more memorable two-day cinema marathon. Film About Killing because it is much starker and more focussed, with the extra material in the cinema version consisting of unnecessary exposition and moralising. My point here is that my judgement, whether you agree with it or not, is based solely on the different structures of the two versions, not, as is usual when comparing film and TV, on different screen ratios or film gauges or the difference between the theatrical and the home viewing experience.

Film About Killing because it is much starker and more focussed, with the extra material in the cinema version consisting of unnecessary exposition and moralising. My point here is that my judgement, whether you agree with it or not, is based solely on the different structures of the two versions, not, as is usual when comparing film and TV, on different screen ratios or film gauges or the difference between the theatrical and the home viewing experience. move which caused controversy at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. So, what we need now is a convergence of critical response and hopefully the Sight and Sound poll will come to be seen as one small step on the way.

move which caused controversy at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. So, what we need now is a convergence of critical response and hopefully the Sight and Sound poll will come to be seen as one small step on the way. Hardy represented in such lists by Sons of the Desert or Way Out West rather than one of the true masterpieces from their catalogue of shorts. As far as I am concerned, there is a right length for everything and, if that is under 40 minutes, so be it. Comedy is a case in point: 30 to 40 minutes, or less, is best for comedy because you can only laugh so much without the effect beginning to wear off. Padding comedy out to feature length by adding musical numbers or romantic sub-plots undermines the structure of the piece.

Hardy represented in such lists by Sons of the Desert or Way Out West rather than one of the true masterpieces from their catalogue of shorts. As far as I am concerned, there is a right length for everything and, if that is under 40 minutes, so be it. Comedy is a case in point: 30 to 40 minutes, or less, is best for comedy because you can only laugh so much without the effect beginning to wear off. Padding comedy out to feature length by adding musical numbers or romantic sub-plots undermines the structure of the piece. creativity in the 30-minute form, coming out of comedy, but containing reflective or dramatic elements, which has been responsible for many of the very best titles on offer. If I was to list my top ten TV titles of this century, it would include The Thick of It, Sensitive Skin, Getting On and Him and Her. Recent outstanding work from the USA includes Transparent, Girls, Master of None and One Mississippi. These series can have similar plot arcs to drama, rather than simply being episodic, and should be judged on the same terms. There is no extra merit in length – succinctness can be the greater skill. This is recognised in the end of year lists of best TV, but it is interesting that the TV titles in the Sight and Sound list are only those where the episodes are of feature length. But I mustn’t grumble – it’s a start.

creativity in the 30-minute form, coming out of comedy, but containing reflective or dramatic elements, which has been responsible for many of the very best titles on offer. If I was to list my top ten TV titles of this century, it would include The Thick of It, Sensitive Skin, Getting On and Him and Her. Recent outstanding work from the USA includes Transparent, Girls, Master of None and One Mississippi. These series can have similar plot arcs to drama, rather than simply being episodic, and should be judged on the same terms. There is no extra merit in length – succinctness can be the greater skill. This is recognised in the end of year lists of best TV, but it is interesting that the TV titles in the Sight and Sound list are only those where the episodes are of feature length. But I mustn’t grumble – it’s a start.

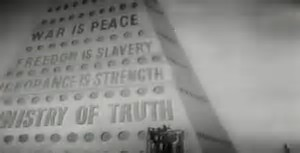

Orwell’s Ministry of Truth was partly based on his experiences at the BBC). The purist in me would like to see captions included in any re-edited programme, explaining what is missing at any point and why, but I realise that is not going to happen. The most extreme example of this sort of process in the current spate of scandals is the re-shooting and re-editing of Ridley Scott’s All the Money in the World to replace the performance of Kevin Spacey with one by Christopher Plummer. The film had been completed but not released, so it isn’t a case of changing something which is already a part of film history, but the digital technology to do just that exists and the temptation to use it may grow. After all, film and TV are collaborative arts and it would be unfair on other contributors if something was withdrawn because of the nefarious activities of one star or producer. The Spacey case looks primarily to be a financial decision, rather than a moral one, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised if, at some future date and if the climate is felt to be right, a “director’s cut” edition appears, with Spacey’s performance reinstated.

Orwell’s Ministry of Truth was partly based on his experiences at the BBC). The purist in me would like to see captions included in any re-edited programme, explaining what is missing at any point and why, but I realise that is not going to happen. The most extreme example of this sort of process in the current spate of scandals is the re-shooting and re-editing of Ridley Scott’s All the Money in the World to replace the performance of Kevin Spacey with one by Christopher Plummer. The film had been completed but not released, so it isn’t a case of changing something which is already a part of film history, but the digital technology to do just that exists and the temptation to use it may grow. After all, film and TV are collaborative arts and it would be unfair on other contributors if something was withdrawn because of the nefarious activities of one star or producer. The Spacey case looks primarily to be a financial decision, rather than a moral one, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised if, at some future date and if the climate is felt to be right, a “director’s cut” edition appears, with Spacey’s performance reinstated. from the very first episode in 1960 had been found guilty of a historic rape charge (or even if his acquittal hadn’t been so decisive) the entire archive of the programme, which represents the greatest fictional social history of the last six decades we possess, may have been compromised.

from the very first episode in 1960 had been found guilty of a historic rape charge (or even if his acquittal hadn’t been so decisive) the entire archive of the programme, which represents the greatest fictional social history of the last six decades we possess, may have been compromised. The case of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle: film history tells us that the two great pioneers of silent film comedy were Chaplin and Keaton, but that could have been very different. Arbuckle’s films were as popular as Chaplin’s and he gave Keaton his start in the business. But the scandal surrounding the death of Virginia Rappe, following a party at Arbuckle’s house, effectively finished both his career and his reputation, despite the fact that he was cleared of rape or any involvement in her death. A nervous studio not only banned, but also destroyed his films – what remains today has been reconstructed from sub-standard copies from the world’s film archives.

The case of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle: film history tells us that the two great pioneers of silent film comedy were Chaplin and Keaton, but that could have been very different. Arbuckle’s films were as popular as Chaplin’s and he gave Keaton his start in the business. But the scandal surrounding the death of Virginia Rappe, following a party at Arbuckle’s house, effectively finished both his career and his reputation, despite the fact that he was cleared of rape or any involvement in her death. A nervous studio not only banned, but also destroyed his films – what remains today has been reconstructed from sub-standard copies from the world’s film archives. his film-making career (in Europe, at least) has been unaffected by the scandal and his previous films remain highly regarded and easily available. Indeed, there has always been a feeling that an artist who draws upon his or her own experiences (and Polanski’s have been considerably more extreme than most), produces more “authentic” work. While not above the law, artists have often considered themselves beyond the norms of socially acceptable behaviour. Not any more.

his film-making career (in Europe, at least) has been unaffected by the scandal and his previous films remain highly regarded and easily available. Indeed, there has always been a feeling that an artist who draws upon his or her own experiences (and Polanski’s have been considerably more extreme than most), produces more “authentic” work. While not above the law, artists have often considered themselves beyond the norms of socially acceptable behaviour. Not any more. starred in? Armando Iannucci’s The Thick of It, in the first season of which he starred as the hapless government minister Hugh Abbot, simply evolved into one of the most brilliant satires of the last decade without him. That first series is available on DVD, though with Peter Capaldi on the cover now, rather than Langham. Paul Whitehouse’s Help on the other hand, in which Langham played a psychiatrist to a variety of characters, all played by Whitehouse, was finished by the case and there was only ever the one season. It was the best thing Whitehouse had done since The Fast Show, but, if you want to see it, the only copy publicly available is on a region 4 DVD at a high price. In the meantime, the release of the second season of People Like Us was delayed and was unheralded when it arrived. So, the approach towards Langham’s existing work was entirely pragmatic and sensitive to potential pitfalls.

starred in? Armando Iannucci’s The Thick of It, in the first season of which he starred as the hapless government minister Hugh Abbot, simply evolved into one of the most brilliant satires of the last decade without him. That first series is available on DVD, though with Peter Capaldi on the cover now, rather than Langham. Paul Whitehouse’s Help on the other hand, in which Langham played a psychiatrist to a variety of characters, all played by Whitehouse, was finished by the case and there was only ever the one season. It was the best thing Whitehouse had done since The Fast Show, but, if you want to see it, the only copy publicly available is on a region 4 DVD at a high price. In the meantime, the release of the second season of People Like Us was delayed and was unheralded when it arrived. So, the approach towards Langham’s existing work was entirely pragmatic and sensitive to potential pitfalls. key question is whether these monuments have become a part of history and, if not, how far back do you have to go before they are regarded as such? Monuments to ancient empires based on slavery – Egypt, Greece and Rome – are treasured and are part of UNESCO heritage sites. The British Empire and the American Civil War have modern resonances which make things more contentious. The comparison may seem extreme, but how far things remain in the public consciousness can affect their place as a part of history. Films and TV programmes can be seen as a kind of audio-visual statuary in this context. If something is deemed to be unsuitable for continued public display, then it should be kept in a museum (for monuments) or an archive (for film and TV). Ideally, the cultural institutions involved will be able to make the materials publicly available with the appropriate contextualisation. It can be awkward and the contextualisation is everything. You either contextualise in public (which is preferable for historic continuity) or make materials available in a controlled museum/archive environment, for scholars only (who will then write the history and include or exclude things according to what they find of interest).

key question is whether these monuments have become a part of history and, if not, how far back do you have to go before they are regarded as such? Monuments to ancient empires based on slavery – Egypt, Greece and Rome – are treasured and are part of UNESCO heritage sites. The British Empire and the American Civil War have modern resonances which make things more contentious. The comparison may seem extreme, but how far things remain in the public consciousness can affect their place as a part of history. Films and TV programmes can be seen as a kind of audio-visual statuary in this context. If something is deemed to be unsuitable for continued public display, then it should be kept in a museum (for monuments) or an archive (for film and TV). Ideally, the cultural institutions involved will be able to make the materials publicly available with the appropriate contextualisation. It can be awkward and the contextualisation is everything. You either contextualise in public (which is preferable for historic continuity) or make materials available in a controlled museum/archive environment, for scholars only (who will then write the history and include or exclude things according to what they find of interest). present episodes of Johnny Speight’s Till Death Us Do Part to a modern audience. It is a crucial television text from the sixties and seventies, which was made with the best intentions and is brilliantly written and performed, but the racism, in particular, is impossible to present without context and pretty difficult with it. What shocks the most is not the language or attitudes presented, but the delighted reaction of the contemporary studio audience. When the BBC re-made a lost episode as part of their sitcom season last year, they struggled to find one which was free of racist references and, having done so, still had to point out to the audience that the sexist attitudes were from another era.

present episodes of Johnny Speight’s Till Death Us Do Part to a modern audience. It is a crucial television text from the sixties and seventies, which was made with the best intentions and is brilliantly written and performed, but the racism, in particular, is impossible to present without context and pretty difficult with it. What shocks the most is not the language or attitudes presented, but the delighted reaction of the contemporary studio audience. When the BBC re-made a lost episode as part of their sitcom season last year, they struggled to find one which was free of racist references and, having done so, still had to point out to the audience that the sexist attitudes were from another era. admiration for his work is on record, particularly Horace and Pete, which I regard as a modern American classic and my view of which is not changed by the recent revelations about his personal behaviour. It is possible to have integrity as an artist even though it may be lacking as a person. Indeed, if the work is dealing with human failings, as the best work so often is, then it can help to understand those failings personally – maybe it is even essential. Louis CK’s I Love You, Daddy may well turn out to be the most relevant piece to emerge from this whole situation – I would say that I can’t wait to see it, but it looks like I’m going to have to – maybe for a very long time.

admiration for his work is on record, particularly Horace and Pete, which I regard as a modern American classic and my view of which is not changed by the recent revelations about his personal behaviour. It is possible to have integrity as an artist even though it may be lacking as a person. Indeed, if the work is dealing with human failings, as the best work so often is, then it can help to understand those failings personally – maybe it is even essential. Louis CK’s I Love You, Daddy may well turn out to be the most relevant piece to emerge from this whole situation – I would say that I can’t wait to see it, but it looks like I’m going to have to – maybe for a very long time.