This time of the year we would usually be fully engaged with the start of the Autumn season, containing multiple new series as well as returning favourites. Alas, the pandemic has so disrupted production that we are likely to be in makeshift mode for some time. Nevertheless, the summer and early autumn have managed to provide a handful of worthwhile new offerings made before the lockdown struck, some maybe held back, others maybe brought forward to fill the yawning gaps in the schedules.

Any time is good to get something new from Jimmy McGovern, but it was particularly welcome in the middle of this arid summer. Anthony (BBC1) was clearly always intended for transmission in July anyway, as it was made to mark the 15th anniversary of the racist murder of Anthony Walker in Liverpool. Mc Govern has such a track record of tackling the city’s major traumas that it was a subject perfect for him, yet the BBC rightly emphasised that Anthony’s mother, Gee Walker, had expressly asked McGovern to do it in case it should be remarked in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement and the question of “white saviours” in fictionalised representations, that it should have been dramatized by a black writer.

Also pertinent in the light of the recent heightened debates about racism was Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You (BBC1), though it was considerably more than that as well. I cannot but agree with all the commentators who hailed it as one of the most significant new dramas of the year, though I have to admit that I’m not completely sure why. This is entirely down to my own limited horizons as an ageing straight white man (with age being the most significant of those four descriptors), rather than any problem with the drama itself. I’m not saying it wasn’t aimed at me – like all great drama it was there to be appreciated by everybody – but rather that it was not within the limits of my full understanding in terms of the detail that makes it a masterpiece: the modern social, cultural and musical references and multiple other subtleties that escaped my comprehension. I do, however, have plenty of experience of judging drama as drama, even in those cases where it doesn’t make an immediate personal connection, and, in terms of its narrative drive I could see that this was obviously something outstanding. I particularly liked the fractured timeline approach, allowing some episodes to stand alone, and the way Coel’s character’s growing appreciation of how to create narrative structure in her own work impacted on her understanding and resolution of what had happened to her, even if it did involve presenting a number of possible endings. A definite for the shortlist.

At the other end of the spectrum, the return of There She Goes (BBC2) for a second season, provided me with something so close to my own personal experience, that I also question my ability to judge it objectively. At the time of the first season, I wrote a blog about this experience (Close to Home, November 14th, 2018) and the second season simply continued in precisely the same vein. Every episode, and particularly the flashback scenes in which Rosie’s disability becomes apparent, once again provided moments of intimate recognition. And Jessica Hynes and David Tennant were again exceptional. I won’t put it on the shortlist again, but it remains my personal favourite.

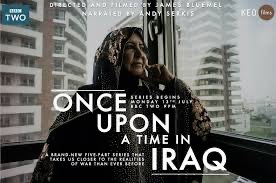

Documentaries are on much safer ground than dramas these days. The things that make an excellent documentary series have remained fairly constant of late and were all clearly on display in the outstanding four-part Once Upon a Time in Iraq (BBC2): strong subject matter; a balanced roster of the most interesting and articulate interviewees; a gripping narrative structure; and the most relevant archive footage. There is little more to say – it wasn’t ground-breaking, just extremely good programme-making, and it’s on the shortlist.

And if you were looking for a series which illustrated a historical period by dramatic reconstruction and which also worked as character-driven drama, then along came Mrs America (FX/BBC2), Dahvi Waller’s account of the struggles between feminists and a conservative women’s group over the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment in the US in the 1970s. Its strengths were also traditional ones – a well-constructed script which gave equal weight to historical context as to character development, subtle touches which underscored both aspects, great attention to period detail and, above all, terrific performances, particularly from Cate Blanchett as the leader of the conservative faction. It was also refreshing to encounter such a series which is clearly not angling for a second season.

All the above were transmitted on the BBC, which has managed to balance its resources well in the extraordinary circumstances of the year. ITV’s most impressive drama offering of the period was Des, a dramatisation of the interrogation and trial of the serial killer Dennis Nilsen. It was clearly inspired by the success of a series like Mindhunter (Netflix), which showed that having such a criminal talk openly to investigators across a desk could be just as chilling, if not more so, than reconstructing his crimes. You need a charismatic actor for it to work well and David Tennant (who seems pretty ubiquitous this year) more than rose to the task.

Most of the above appeared during mid to late summer. The most interesting of the early autumn offerings are on subscription and streaming platforms and are ongoing at the time of writing, so I may well have to return to them later. And the most interesting of those is Lovecraft Country (HBO/Sky Atlantic), which counts Jordan Peele and J.J.Abrams amongst its executive producers, and does it ever show. A mixture of social comment on the history of racism and outrageous horror/fantasy with terrific effects, it never fails to startle, though its ultimate destination remains (so far) a mystery. Meanwhile, I Hate Suzie (Sky Atlantic) is superficially similar to I May Destroy You, and I have many of the same problems with it, though without the clear conviction this time that I am watching something of significance, but I will stick with it just in case.

I have, on several occasions, used this blog to sing the praises of Channel 4’s Utopia and to lament the fact that it was cancelled before completion (and, indeed, to hope that it may at some stage be continued). So, I was bound to be attracted to Gillian Flynn’s American re-make (Amazon), if only to check it out for comparison. Unsurprisingly, it is not a patch on the original (how could it possibly be?), but I’m certainly sticking with it for the duration, if only in the hope that the story will be completed.

The pandemic has, of course, thrown greater responsibility onto TV archives to fill the schedules. Most of this has involved straight repeats or compilations, but, in some instances, has inspired developments in the creative use of archival material. Louis Theroux: Life on the Edge (BBC2) was a series of four in which the documentary-maker looked back thematically at his career and reflected thoughtfully on the meaning of the shows he had made, while at the same time, catching up on-line with many of those whose lives he had explored in order to get their take as well. It was a simple idea, but very effectively and movingly executed. Preceding it on BBC2 on Sundays, was Harry Hill’s World of TV, a laugh-out-loud dissection of different TV genes – another simple idea beautifully delivered, thanks to what must have been exhaustive archival research. I particularly liked the sequences in which he played multiple examples of recurring tropes, such as the large number of highly respected crime dramas which have advanced their plots by having somebody enter a room and dramatically announce “so-and-so has regained consciousness”.

But, the most creative use of archive came along just a couple of nights ago with John Wyver’s 50thanniversary documentary about Play for Today, Drama Out of a Crisis (BBC4). The density of the high definition 16:9 screen was fully employed to cram into its 90-minute span as much material as this legendary strand deserved, all of it presented and framed in its original transmission ratio and selected to illustrate the points being made as effectively as possible. And, of course, the anniversary is also a great excuse for the BBC to transmit the best archival repeats of the lockdown, though they probably would have done so in “normal” circumstances anyway.

letter to the start: John Adams is one of three living American composers whose works feature strongly in my collection (Glass and Reich being the others). Adams’ works are highly contemporary and witty, much like the man himself – I once saw him conduct a programme of Frank Zappa pieces at the Proms while carrying on a dialogue with the audience. He has cornered the market in operas and performance pieces based on events from recent history – Nixon in China is probably his masterpiece, but I particularly enjoyed re-visiting his 1995 piece about the 1994 Los Angeles earthquake, I Was Looking at the Ceiling and then I Saw the Sky. One of the best things about contemporary composers like Adams, Reich and Glass is that there is often only one recording of any particular work to choose from. As they are composers of the recording age, these can be regarded as definitive versions, though in the case of all three, newer recordings of some key works are emerging, which gives a hint as to which of them may become “classics”.

letter to the start: John Adams is one of three living American composers whose works feature strongly in my collection (Glass and Reich being the others). Adams’ works are highly contemporary and witty, much like the man himself – I once saw him conduct a programme of Frank Zappa pieces at the Proms while carrying on a dialogue with the audience. He has cornered the market in operas and performance pieces based on events from recent history – Nixon in China is probably his masterpiece, but I particularly enjoyed re-visiting his 1995 piece about the 1994 Los Angeles earthquake, I Was Looking at the Ceiling and then I Saw the Sky. One of the best things about contemporary composers like Adams, Reich and Glass is that there is often only one recording of any particular work to choose from. As they are composers of the recording age, these can be regarded as definitive versions, though in the case of all three, newer recordings of some key works are emerging, which gives a hint as to which of them may become “classics”.

would be ahead of them both – mental note to rectify this!). I had about 6 months of Bach-accompanied driving, starting with the Brandenburgs at the beginning of a football season and culminating in his oratorios and masses in time for Easter. I think John Eliot Gardiner’s rendition of the B-minor Mass must be amongst my most treasured recordings and this is another point of the exercise – to identify those works and recordings I will want to revisit, ideally in live performance, and those I can probably put behind me. My Bach collection also contains a number of “traditional” performances, contrasted with those on period instruments. I tend to prefer the latter, especially when the performance history has been well researched by somebody like Gardiner or Herreweghe. The Brandenburg Concertos are a case in point, as I have two recordings, one by the Berlin Phil under Karajan and the other with the English Concert under Trevor Pinnock (both on DG). The Karajan is pompous and overblown, where the Pinnock sounds like the true voice of Bach. I know which one is now behind me.

would be ahead of them both – mental note to rectify this!). I had about 6 months of Bach-accompanied driving, starting with the Brandenburgs at the beginning of a football season and culminating in his oratorios and masses in time for Easter. I think John Eliot Gardiner’s rendition of the B-minor Mass must be amongst my most treasured recordings and this is another point of the exercise – to identify those works and recordings I will want to revisit, ideally in live performance, and those I can probably put behind me. My Bach collection also contains a number of “traditional” performances, contrasted with those on period instruments. I tend to prefer the latter, especially when the performance history has been well researched by somebody like Gardiner or Herreweghe. The Brandenburg Concertos are a case in point, as I have two recordings, one by the Berlin Phil under Karajan and the other with the English Concert under Trevor Pinnock (both on DG). The Karajan is pompous and overblown, where the Pinnock sounds like the true voice of Bach. I know which one is now behind me.

Harmonia Mundi recordings, which I got for under £30 when it came out (you’d pay much more now) and which greatly increased my Bach collection at a stroke. His performances and the recordings of them are outstanding. This is one of several such bargain boxes I have acquired – others are devoted to Rafael Kubelik at DG, Bernard Haitink (live Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra recordings) and Leonard Bernstein – which is another reason for my slow progress through the collection.

Harmonia Mundi recordings, which I got for under £30 when it came out (you’d pay much more now) and which greatly increased my Bach collection at a stroke. His performances and the recordings of them are outstanding. This is one of several such bargain boxes I have acquired – others are devoted to Rafael Kubelik at DG, Bernard Haitink (live Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra recordings) and Leonard Bernstein – which is another reason for my slow progress through the collection. of Beethoven’s works, including three complete symphony cycles (by Karajan, Gardiner and in the aforementioned Kubelik set), plus three additional copies of the ninth (yes, I know!) meant that I had to space them out between the concertos, string quartets, piano sonatas usw. Much the same goes for my all-time favourite choral work – the Missa Solemnis (four different versions, including in the Herreweghe and Haitink sets, but Gardiner’s remains my top preference, though Haitink runs him close). The period instrument question is also pertinent to Beethoven and there has been a lot of scholarly research behind the question of interpretation and tempi by the likes of Gardiner, Norrington and Harnoncourt. When Gardiner’s symphony cycle was released, I was knocked out – hearing such familiar works so completely newly and excitingly presented was a revelation. I remember a news item at the time that Gardiner’s aunt (or maybe it was his godmother) was caught speeding and in court gave as her (very reasonable) excuse that she was so excited by listening to this set: if ever anybody deserved to get off without a fine it was her (she didn’t). Listening to Gardiner’s Beethoven 9 also reminded me of one of my favourite Proms of recent years – when Gardiner made the string section of the orchestra perform the entire work standing up! I have a simple answer to anybody who doubts the value of period instrument performances – Beethoven (or whoever) knew what he was doing.

of Beethoven’s works, including three complete symphony cycles (by Karajan, Gardiner and in the aforementioned Kubelik set), plus three additional copies of the ninth (yes, I know!) meant that I had to space them out between the concertos, string quartets, piano sonatas usw. Much the same goes for my all-time favourite choral work – the Missa Solemnis (four different versions, including in the Herreweghe and Haitink sets, but Gardiner’s remains my top preference, though Haitink runs him close). The period instrument question is also pertinent to Beethoven and there has been a lot of scholarly research behind the question of interpretation and tempi by the likes of Gardiner, Norrington and Harnoncourt. When Gardiner’s symphony cycle was released, I was knocked out – hearing such familiar works so completely newly and excitingly presented was a revelation. I remember a news item at the time that Gardiner’s aunt (or maybe it was his godmother) was caught speeding and in court gave as her (very reasonable) excuse that she was so excited by listening to this set: if ever anybody deserved to get off without a fine it was her (she didn’t). Listening to Gardiner’s Beethoven 9 also reminded me of one of my favourite Proms of recent years – when Gardiner made the string section of the orchestra perform the entire work standing up! I have a simple answer to anybody who doubts the value of period instrument performances – Beethoven (or whoever) knew what he was doing.

works on Sony, I was able to appreciate his versatility and enjoy pieces I had not previously encountered, such as the Mass of Life. I was also able to contrast three versions of his masterpiece, West Side Story – theatrical (original Broadway cast), cinematic (movie soundtrack) and operatic (which I cannot listen to without seeing Humphrey Burton’s wonderful Omnibus documentary about its making in my mind’s eye).

works on Sony, I was able to appreciate his versatility and enjoy pieces I had not previously encountered, such as the Mass of Life. I was also able to contrast three versions of his masterpiece, West Side Story – theatrical (original Broadway cast), cinematic (movie soundtrack) and operatic (which I cannot listen to without seeing Humphrey Burton’s wonderful Omnibus documentary about its making in my mind’s eye). ever got out of his concertos and symphonies. The 2nd Symphony has some nice things, but it seems to me that the movements of his symphonies are pretty much interchangeable – none of the four has any real identity. But that one exceptional work makes his whole career worthwhile! I have three copies of the German Requiem and never thought I would listen to anybody’s version other than Gardiner’s on DG until I got my Herreweghe Harmonia Mundi set. Truth be told, there is little between them, but Herreweghe’s sheer attack in “Denn wir haben…” gives him the edge.

ever got out of his concertos and symphonies. The 2nd Symphony has some nice things, but it seems to me that the movements of his symphonies are pretty much interchangeable – none of the four has any real identity. But that one exceptional work makes his whole career worthwhile! I have three copies of the German Requiem and never thought I would listen to anybody’s version other than Gardiner’s on DG until I got my Herreweghe Harmonia Mundi set. Truth be told, there is little between them, but Herreweghe’s sheer attack in “Denn wir haben…” gives him the edge.

the best things to listen to while driving – Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet (in the 70 minute version with Tom Waits) basically repeats the same brief recording of a tramp singing a simple hymn over and over again, while Bryars weaves a wonderfully affecting accompaniment around it throughout and Waits improvises his own at the end. The Sinking of the Titanic is of similar length and approach, though with more variation and density.

the best things to listen to while driving – Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet (in the 70 minute version with Tom Waits) basically repeats the same brief recording of a tramp singing a simple hymn over and over again, while Bryars weaves a wonderfully affecting accompaniment around it throughout and Waits improvises his own at the end. The Sinking of the Titanic is of similar length and approach, though with more variation and density.

brilliantly acted and directed; dialogue which seemed highly conventional rather than being idiomatic of “today’s young people”; lovingly photographed Irish rural landscapes and Dublin vistas. It also allowed a chance to compare the styles of the two excellent directors who realised it – Lenny Abrahamson for the first six episodes and Hettie Macdonald for the remaining six. Would it be a case of the male vs the female gaze? Abrahamson’s approach seemed the more restrained – the pace was slower and the characters artfully framed, with Marianne (Daisy Edgar-Jones) shot in softer focus and often backlit, to emphasise her fragility, while Connell (Paul Mescal) was regularly lit from the side to emphasise his strong features. Macdonald’s episodes were stronger on the key scenes and moved the plot more briskly (she is a veteran of Doctor Who). Of course, this difference was almost certainly down to the content of the episodes, as plot developments came more regularly later in the series, as well as some important location shifts, including Italy and Sweden. However, the fact that two of the MacDonald episodes came in at 25 minutes, while the rest were 30, would seem to bear out my observation, at least in part.

brilliantly acted and directed; dialogue which seemed highly conventional rather than being idiomatic of “today’s young people”; lovingly photographed Irish rural landscapes and Dublin vistas. It also allowed a chance to compare the styles of the two excellent directors who realised it – Lenny Abrahamson for the first six episodes and Hettie Macdonald for the remaining six. Would it be a case of the male vs the female gaze? Abrahamson’s approach seemed the more restrained – the pace was slower and the characters artfully framed, with Marianne (Daisy Edgar-Jones) shot in softer focus and often backlit, to emphasise her fragility, while Connell (Paul Mescal) was regularly lit from the side to emphasise his strong features. Macdonald’s episodes were stronger on the key scenes and moved the plot more briskly (she is a veteran of Doctor Who). Of course, this difference was almost certainly down to the content of the episodes, as plot developments came more regularly later in the series, as well as some important location shifts, including Italy and Sweden. However, the fact that two of the MacDonald episodes came in at 25 minutes, while the rest were 30, would seem to bear out my observation, at least in part. capabilities. I have no such qualms about the second season, which is in much the same vein, but which now looks like a fully settled sitcom. Characters who had existed mainly in the background of the narrative (and are played by some outstanding performers) were given greater weight this time around, so that it felt more like an ensemble piece. The melancholy feel was still there, but there were considerably more laughs – some sequences, most notably the climactic talent show, had me in tears of laughter. Paul Kaye’s psychiatrist was revealed as a distant cousin of The Office’s Finchy, while Ethan Lawrence as James is clearly the new James Corden (as if we needed one). I’m really pleased to add it to the shortlist.

capabilities. I have no such qualms about the second season, which is in much the same vein, but which now looks like a fully settled sitcom. Characters who had existed mainly in the background of the narrative (and are played by some outstanding performers) were given greater weight this time around, so that it felt more like an ensemble piece. The melancholy feel was still there, but there were considerably more laughs – some sequences, most notably the climactic talent show, had me in tears of laughter. Paul Kaye’s psychiatrist was revealed as a distant cousin of The Office’s Finchy, while Ethan Lawrence as James is clearly the new James Corden (as if we needed one). I’m really pleased to add it to the shortlist.

without its studio audience at first, but as it adapted, the standard of the humour rose. I have always contended that the true sign of whether something is funny is when you experience it without anybody else laughing and thus prompting your own laughter, and HIGNFY made me laugh out loud many times during its recent socially-distanced run – in particular, Paul Merton’s dry asides were more easily audible than usual. Later, on Friday evenings, The Graham Norton Show (BBC1) proved that it is Norton’s interviewing skills, rather than the interaction of his guests, which is the real secret of the show’s success. But my favourite adapted show of the lockdown has to be Match of the Day

without its studio audience at first, but as it adapted, the standard of the humour rose. I have always contended that the true sign of whether something is funny is when you experience it without anybody else laughing and thus prompting your own laughter, and HIGNFY made me laugh out loud many times during its recent socially-distanced run – in particular, Paul Merton’s dry asides were more easily audible than usual. Later, on Friday evenings, The Graham Norton Show (BBC1) proved that it is Norton’s interviewing skills, rather than the interaction of his guests, which is the real secret of the show’s success. But my favourite adapted show of the lockdown has to be Match of the Day

Stori

Stori

Mangan series Hang-Ups did much the same a couple of years ago). Also, there was a more didactic and drama-doc feel about the series: the writers were often making points about the crisis rather than using it as a backdrop for the drama – a worthwhile thing to do, for sure, but not as satisfying as the real drama of Isolation Stories, from which similar points emerged without feeling forced.

Mangan series Hang-Ups did much the same a couple of years ago). Also, there was a more didactic and drama-doc feel about the series: the writers were often making points about the crisis rather than using it as a backdrop for the drama – a worthwhile thing to do, for sure, but not as satisfying as the real drama of Isolation Stories, from which similar points emerged without feeling forced.

starting points and the stories, characters and setting are, as far as I can see, all down to writer/creator Nathaniel Halpern. Halpern has the great gift of being able to establish a character in a minimal time frame (much as Jimmy McGovern does in The Street and Accused) and this is vital to the structure of the series, which consists of 8 episodes, each of which tells a separate story, though they are linked by the location, the relationships of the characters and the presence of The Loop (the research facility built to unlock and explore the mysteries of the universe). Characters glimpsed briefly in early episodes return at the centre of their own stories as the series proceeds. The characters who return most often are The Loop’s founder, Russ (Jonathan Pryce), his daughter-in-law Loretta (Rebecca Hall), who takes his position later in the series and her young son Cole (Duncan Joiner), through whose eyes much of the mystery is seen.

starting points and the stories, characters and setting are, as far as I can see, all down to writer/creator Nathaniel Halpern. Halpern has the great gift of being able to establish a character in a minimal time frame (much as Jimmy McGovern does in The Street and Accused) and this is vital to the structure of the series, which consists of 8 episodes, each of which tells a separate story, though they are linked by the location, the relationships of the characters and the presence of The Loop (the research facility built to unlock and explore the mysteries of the universe). Characters glimpsed briefly in early episodes return at the centre of their own stories as the series proceeds. The characters who return most often are The Loop’s founder, Russ (Jonathan Pryce), his daughter-in-law Loretta (Rebecca Hall), who takes his position later in the series and her young son Cole (Duncan Joiner), through whose eyes much of the mystery is seen.

slow, so that all the implications of what we are seeing sink in. The cinematography is very beautiful and there is a Malick-style focus on the natural world and the placing of characters in landscapes. Music is very important – it is by Philip Glass (who you know well is one of my very favourites) and Paul Leonard-Morgan and both their contributions are perfectly integrated and affecting. In keeping with, and contributing to the mood of the piece, the music is slow and beautiful.

slow, so that all the implications of what we are seeing sink in. The cinematography is very beautiful and there is a Malick-style focus on the natural world and the placing of characters in landscapes. Music is very important – it is by Philip Glass (who you know well is one of my very favourites) and Paul Leonard-Morgan and both their contributions are perfectly integrated and affecting. In keeping with, and contributing to the mood of the piece, the music is slow and beautiful.

everything you could want: direction by Stephen Frears, again tackling in a three-part TV series the sort of real-life drama he has excelled at so many times; a terrific story – the attempt to defraud (or maybe not?) the mega hit quiz show of the turn of the century, Who Wants to be a Millionaire? (ITV); a brilliant cast, headed by Matthew MacFadyen and Sian Clifford and including another spot-on cameo from Michael Sheen as Chris Tarrant. Like the programme it depicted, it was cleverly “stripped” across three nights and was unmissable. And, of course, it delivered in spades. Whether that makes it a candidate for the shortlist, I’m not fully convinced, but, as the list is so short right now, it’s going in anyway. At the end of the day, there is no such thing as a sure-fire success and, even though this is about the nearest you could get to that, it is still a terrific achievement. So, we are up to 4!

everything you could want: direction by Stephen Frears, again tackling in a three-part TV series the sort of real-life drama he has excelled at so many times; a terrific story – the attempt to defraud (or maybe not?) the mega hit quiz show of the turn of the century, Who Wants to be a Millionaire? (ITV); a brilliant cast, headed by Matthew MacFadyen and Sian Clifford and including another spot-on cameo from Michael Sheen as Chris Tarrant. Like the programme it depicted, it was cleverly “stripped” across three nights and was unmissable. And, of course, it delivered in spades. Whether that makes it a candidate for the shortlist, I’m not fully convinced, but, as the list is so short right now, it’s going in anyway. At the end of the day, there is no such thing as a sure-fire success and, even though this is about the nearest you could get to that, it is still a terrific achievement. So, we are up to 4! a magnificent resource and the concerts are beautifully presented visually – so much so that you really feel you are getting to know the individual instrumentalists and making it something that must be watched as well as listened to (though I often do listen while composing this blog). I also took in the complete Vienna State Opera Ring cycle (fine performances – lousy production) and, over the Easter weekend, an excellent stadium-style production of Jesus Christ Superstar.

a magnificent resource and the concerts are beautifully presented visually – so much so that you really feel you are getting to know the individual instrumentalists and making it something that must be watched as well as listened to (though I often do listen while composing this blog). I also took in the complete Vienna State Opera Ring cycle (fine performances – lousy production) and, over the Easter weekend, an excellent stadium-style production of Jesus Christ Superstar.

getting out of problems, like going back in time and changing things were being deployed. I had nothing against Jodie Whitaker’s doctor, but talk of who would come after her was already beginning to surface – it seems that any actor in this role needs to indicate they are leaving only just after they start, probably as a way of insuring that they are still considered for other roles. Indeed, I did give up watching, only to be lured back by the revelation about another Doctor and I did find the concluding Cybermen episodes highly engaging.

getting out of problems, like going back in time and changing things were being deployed. I had nothing against Jodie Whitaker’s doctor, but talk of who would come after her was already beginning to surface – it seems that any actor in this role needs to indicate they are leaving only just after they start, probably as a way of insuring that they are still considered for other roles. Indeed, I did give up watching, only to be lured back by the revelation about another Doctor and I did find the concluding Cybermen episodes highly engaging.

Picard, just finished on Amazon, was a brilliant re-boot of The Next Generation, presented as a ten-part story (in other words, like an extended movie rather than the classic series format). Production values matched the latest big-budget sci-fi potential, while the story gripped from first to last and the performances were impeccable. Nostalgia was given its space but did not get in the way of the developing narrative. And, philosophically, it had much more to say about artificial intelligence and humanity than any number of seasons of Westworld. The final scene between Picard and Data was just beautiful.

Picard, just finished on Amazon, was a brilliant re-boot of The Next Generation, presented as a ten-part story (in other words, like an extended movie rather than the classic series format). Production values matched the latest big-budget sci-fi potential, while the story gripped from first to last and the performances were impeccable. Nostalgia was given its space but did not get in the way of the developing narrative. And, philosophically, it had much more to say about artificial intelligence and humanity than any number of seasons of Westworld. The final scene between Picard and Data was just beautiful.

not quite as impactfully as it was the same time last year with its fourth. It seems curmudgeonly to criticise something which delivers so regularly, and there were three Number 9 classics in this year’s bunch (The Referee’s a Wanker, Love’s Great Adventure and Thinking Out Loud) but, having included it in last year’s top ten, it would have had to improve on that season (almost impossible) to get in again this year.

not quite as impactfully as it was the same time last year with its fourth. It seems curmudgeonly to criticise something which delivers so regularly, and there were three Number 9 classics in this year’s bunch (The Referee’s a Wanker, Love’s Great Adventure and Thinking Out Loud) but, having included it in last year’s top ten, it would have had to improve on that season (almost impossible) to get in again this year. central situation – the travails of a Syrian asylum-seeker in Britain – does not overwhelm the narrative. Indeed, in this season it became just a part of a traditional-seeming family sitcom, in which every character is rounded and has an engaging story. It can be very moving, but also devastatingly funny, and moves effortlessly beween those two states.

central situation – the travails of a Syrian asylum-seeker in Britain – does not overwhelm the narrative. Indeed, in this season it became just a part of a traditional-seeming family sitcom, in which every character is rounded and has an engaging story. It can be very moving, but also devastatingly funny, and moves effortlessly beween those two states.

have to say, but rather the entertainment value of how they say it. But how did we get from interviewing managers to VAR.? Well, it’s not difficult to see it. In the pre-VAR days, one of the greatest excuses a manager could have for his team’s failure was refereeing error. If video replays showed that his team had suffered an injustice, he would inevitably call for the introduction of technology to rectify such a fault (and simultaneously distract attention from talking about his team’s failure). On the other hand, the opposing manager would not have seen it or watched it back – Arsene Wenger was the finest exponent of the chutzpah required to deliver a line like this. Inevitably, every manager was at some point driven to call for the use of technology rather than admit to his team’s failings and the journalists amplified the clamour. “Guardiola demands introduction of video technology” screamed the headline – repeated every Sunday or Monday with a different manager’s name until the pressure to do so became irresistible. And so we got VAR. And now it gets the blame from the same mouths which demanded it.

have to say, but rather the entertainment value of how they say it. But how did we get from interviewing managers to VAR.? Well, it’s not difficult to see it. In the pre-VAR days, one of the greatest excuses a manager could have for his team’s failure was refereeing error. If video replays showed that his team had suffered an injustice, he would inevitably call for the introduction of technology to rectify such a fault (and simultaneously distract attention from talking about his team’s failure). On the other hand, the opposing manager would not have seen it or watched it back – Arsene Wenger was the finest exponent of the chutzpah required to deliver a line like this. Inevitably, every manager was at some point driven to call for the use of technology rather than admit to his team’s failings and the journalists amplified the clamour. “Guardiola demands introduction of video technology” screamed the headline – repeated every Sunday or Monday with a different manager’s name until the pressure to do so became irresistible. And so we got VAR. And now it gets the blame from the same mouths which demanded it. strikers through injury. Mourinho had lamented the absence of his stars whereas Dyche had seen it as an opportunity for their replacements to shine. But the reason for this difference of approach was not hard to find – Mourinho’s team had lost; Dyche’s team had won. If the results had been reversed, I can guarantee you the “opinions” would have been as well.

strikers through injury. Mourinho had lamented the absence of his stars whereas Dyche had seen it as an opportunity for their replacements to shine. But the reason for this difference of approach was not hard to find – Mourinho’s team had lost; Dyche’s team had won. If the results had been reversed, I can guarantee you the “opinions” would have been as well.

(and the opposite), but so be it, just as when the ball is shown to have (probably) been hitting the outside of leg stump a denied lbw is still denied because it was the umpire’s decision. The technology is just not reliable enough for some of the forensically marginal decisions we have had. The same should go for handball decisions, but here the change of law is as responsible for the problems as the VAR technology. Also, as with cricket, VAR usage could be limited to a number of challenges allowed to each side during a game.

(and the opposite), but so be it, just as when the ball is shown to have (probably) been hitting the outside of leg stump a denied lbw is still denied because it was the umpire’s decision. The technology is just not reliable enough for some of the forensically marginal decisions we have had. The same should go for handball decisions, but here the change of law is as responsible for the problems as the VAR technology. Also, as with cricket, VAR usage could be limited to a number of challenges allowed to each side during a game.

earliest masterpiece, Fleabag – whereby the central character’s fourth-wall-breaking habits (Fleabag’s looks to camera, Elliot’s narration) are challenged by another character (Fleabag’s love interest and Elliot’s doppelganger respectively) to unsettling effect. Indeed, the finale of Mr Robot was all about making us, the audience, complicit in the action. “Is this real” was the question constantly being asked by both the characters and ourselves and the only reliable answer must be “of course not – it’s a TV series”. At the end it didn’t matter how much of what we had seen had been a construct of Eliot’s mind, because it was wildly entertaining and engaging – just as a great TV series should be. I liked the nod to 2001: A Space Odyssey, too. Not just one of the year’s best, but one of the decade’s (and I’ll be back to that).

earliest masterpiece, Fleabag – whereby the central character’s fourth-wall-breaking habits (Fleabag’s looks to camera, Elliot’s narration) are challenged by another character (Fleabag’s love interest and Elliot’s doppelganger respectively) to unsettling effect. Indeed, the finale of Mr Robot was all about making us, the audience, complicit in the action. “Is this real” was the question constantly being asked by both the characters and ourselves and the only reliable answer must be “of course not – it’s a TV series”. At the end it didn’t matter how much of what we had seen had been a construct of Eliot’s mind, because it was wildly entertaining and engaging – just as a great TV series should be. I liked the nod to 2001: A Space Odyssey, too. Not just one of the year’s best, but one of the decade’s (and I’ll be back to that).

then I didn’t expect to be giving up after the customary 5 episodes I usually give to something which has clear pedigree and promise and which has received a positive welcome from sources I respect (as well as the wider critical community), but which just did not work for me. Watchmen (HBO/Sky Atlantic) suffers from the same problems I identified previously with The Handmaid’s Tale: it is so much in love with its own central concept and the visual realisation of that concept that it neglects the fundamental building blocks of plot and character development – something you can get away with in cinema, but not in an extended series. This may be because the original source material is, quite literally, two-dimensional, but the screenwriters, directors and actors are there to adapt that material for TV presentation and obviously have the skills to do so. However, the writers and directors of Watchmen seem too keen on the visuals and on drawing clever parallels with aspects of our troubled times, while the performers are hamstrung by having to wear masks for much of the time – precisely the reasons, I think, why we have recently heard criticism of superhero movies from masters like Scorsese and Coppola.

then I didn’t expect to be giving up after the customary 5 episodes I usually give to something which has clear pedigree and promise and which has received a positive welcome from sources I respect (as well as the wider critical community), but which just did not work for me. Watchmen (HBO/Sky Atlantic) suffers from the same problems I identified previously with The Handmaid’s Tale: it is so much in love with its own central concept and the visual realisation of that concept that it neglects the fundamental building blocks of plot and character development – something you can get away with in cinema, but not in an extended series. This may be because the original source material is, quite literally, two-dimensional, but the screenwriters, directors and actors are there to adapt that material for TV presentation and obviously have the skills to do so. However, the writers and directors of Watchmen seem too keen on the visuals and on drawing clever parallels with aspects of our troubled times, while the performers are hamstrung by having to wear masks for much of the time – precisely the reasons, I think, why we have recently heard criticism of superhero movies from masters like Scorsese and Coppola. Philip Pulman’s novels by the prolific and excellent Jack Thorne (and what a year he has had with The Virtues, The Accident and now this), it contains epic effects, talking animals and mystical themes, yet its characters are all-too-human. It also has one of the most arresting title sequences since The Night Manager. And it reminded me, in many aspects, of Netflix’s Stranger Things, not least the remarkable similarity in both looks and performance between Dafne Keen and Millie Bobby Brown.

Philip Pulman’s novels by the prolific and excellent Jack Thorne (and what a year he has had with The Virtues, The Accident and now this), it contains epic effects, talking animals and mystical themes, yet its characters are all-too-human. It also has one of the most arresting title sequences since The Night Manager. And it reminded me, in many aspects, of Netflix’s Stranger Things, not least the remarkable similarity in both looks and performance between Dafne Keen and Millie Bobby Brown. completely new take on the overly familiar material. It achieved its effect primarily through an impressive visual imagining of a devastated Edwardian landscape and, as it only ran to three hour-long parts, the makers were able to strike a perfect balance between the human story and the visualisation.

completely new take on the overly familiar material. It achieved its effect primarily through an impressive visual imagining of a devastated Edwardian landscape and, as it only ran to three hour-long parts, the makers were able to strike a perfect balance between the human story and the visualisation. beautifully scanned black and white photographs, the authoritative voice of Peter Coyote. But the longer it went on, the more I got the feeling that this was not the best choice of subject for such lengthy treatment. Compared to Jazz (PBS, 2001), there just wasn’t the depth of interest to be explored. Country Music also seemed to promise at the start of each episode that it would be tracing a link between the music and American social history (as Jazz had done so well), but most of what we got was just the lives and careers of the stars. As before with a Burns series, the BBC is giving us the cut down (9 hours!) version – I have usually sought out the full version (18 hours in this case) but will not be bothering this time. Maybe my problem is that it is not a style of music which interests me greatly, but I do normally expect more from Burns.

beautifully scanned black and white photographs, the authoritative voice of Peter Coyote. But the longer it went on, the more I got the feeling that this was not the best choice of subject for such lengthy treatment. Compared to Jazz (PBS, 2001), there just wasn’t the depth of interest to be explored. Country Music also seemed to promise at the start of each episode that it would be tracing a link between the music and American social history (as Jazz had done so well), but most of what we got was just the lives and careers of the stars. As before with a Burns series, the BBC is giving us the cut down (9 hours!) version – I have usually sought out the full version (18 hours in this case) but will not be bothering this time. Maybe my problem is that it is not a style of music which interests me greatly, but I do normally expect more from Burns. Netflix series Our Planet, which gave us not just spectacular sequences, but also ecological comment. Then there was Attenborough’s personal single doc on climate change for the BBC. So, Seven Worlds, One Planet (BBC1) was simply a re-hash of what we had already had and many sequences were overly familiar – not just the penguins and albatross searching for their chicks or the co-ordinated dancing birds, but even the walruses falling off cliffs which we had already seen earlier in the year. And the material on climate change became less prominent as the series progressed and seemed to have been added almost as an afterthought.

Netflix series Our Planet, which gave us not just spectacular sequences, but also ecological comment. Then there was Attenborough’s personal single doc on climate change for the BBC. So, Seven Worlds, One Planet (BBC1) was simply a re-hash of what we had already had and many sequences were overly familiar – not just the penguins and albatross searching for their chicks or the co-ordinated dancing birds, but even the walruses falling off cliffs which we had already seen earlier in the year. And the material on climate change became less prominent as the series progressed and seemed to have been added almost as an afterthought.

already own). The oldest titles are from the seventies, but there aren’t many of them and they are the usual suspects (Fawlty Towers etc). Most of the material is much more recent. Rather bizarrely, if you click on “search by decade”, you find much more material set in the sixties and seventies (like Cilla or Life on Mars) than made in those decades.

already own). The oldest titles are from the seventies, but there aren’t many of them and they are the usual suspects (Fawlty Towers etc). Most of the material is much more recent. Rather bizarrely, if you click on “search by decade”, you find much more material set in the sixties and seventies (like Cilla or Life on Mars) than made in those decades. launched and a particular lure to myself) and very little factual material of any great interest. It looks as if it has been thrown together in a hurry and sent before its time into the world. It may (just) make sense if it was available to the whole world (much as Netflix was attractive for its archive of American TV before it became a powerhouse of original production), but it isn’t – you have to be located in the UK to access it, though a US version has been available in North America for a couple of years. There has been very little in the way of marketing for Britbox on the BBC or ITV – maybe when Channel 4 joins in next Spring there will be a re-launch, though I doubt they will bring much more to the table.

launched and a particular lure to myself) and very little factual material of any great interest. It looks as if it has been thrown together in a hurry and sent before its time into the world. It may (just) make sense if it was available to the whole world (much as Netflix was attractive for its archive of American TV before it became a powerhouse of original production), but it isn’t – you have to be located in the UK to access it, though a US version has been available in North America for a couple of years. There has been very little in the way of marketing for Britbox on the BBC or ITV – maybe when Channel 4 joins in next Spring there will be a re-launch, though I doubt they will bring much more to the table. However, although this is an understandable concern, I am much more bothered about the absence of key titles from my DVD and blu-ray shelves than from the cinema, which is another, but less remarked, effect of Netflix’s exclusivity policies. My complete collection of Coen brothers films is incomplete without The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, and my Scorsese collection would be similarly so without The Irishman. A glimmer of hope is offered by the welcome recent announcement of a special Criterion edition of Alfonso Cuaron’s Roma in the new year, so maybe it will become a case of waiting and hoping that the niche collector’s market delivers the desired titles.

However, although this is an understandable concern, I am much more bothered about the absence of key titles from my DVD and blu-ray shelves than from the cinema, which is another, but less remarked, effect of Netflix’s exclusivity policies. My complete collection of Coen brothers films is incomplete without The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, and my Scorsese collection would be similarly so without The Irishman. A glimmer of hope is offered by the welcome recent announcement of a special Criterion edition of Alfonso Cuaron’s Roma in the new year, so maybe it will become a case of waiting and hoping that the niche collector’s market delivers the desired titles.